The Dark Art of War Profiteering

War profiteering, often regarded as a shadowy and immoral enterprise, thrives on the despair and destruction wrought by conflicts around the world. This dark art is not a product of modern warfare but a timeless phenomenon, with historical roots tracing back to when the first empires were built on conquest and subjugation.

In contemporary settings, the mechanisms of war profiteering have evolved, leveraging advanced technology, global financial systems, and intricate legal structures to maximize profits. The vested interests of corporations and individuals in prolonging conflicts for financial gain present a grave moral dilemma. It raises profound ethical questions about the role of profit in the context of human suffering and the integrity of those who stand to gain from the perpetuation of violence.

War isn’t just a geopolitical conflict. For many, it’s a lucrative business, saddeningly ushered by people who should protect the common interest. The deep financial involvement of influential companies like Halliburton, Parsons, and Bechtel in the Iraq War is a drop in the vast ocean of machinations on the global warfare stage.

In this article, I’ll explore how the elite profit from world conflicts and why we, as a society, must question and challenge this unethical underbelly of global crises.

Capitalizing on Calamity

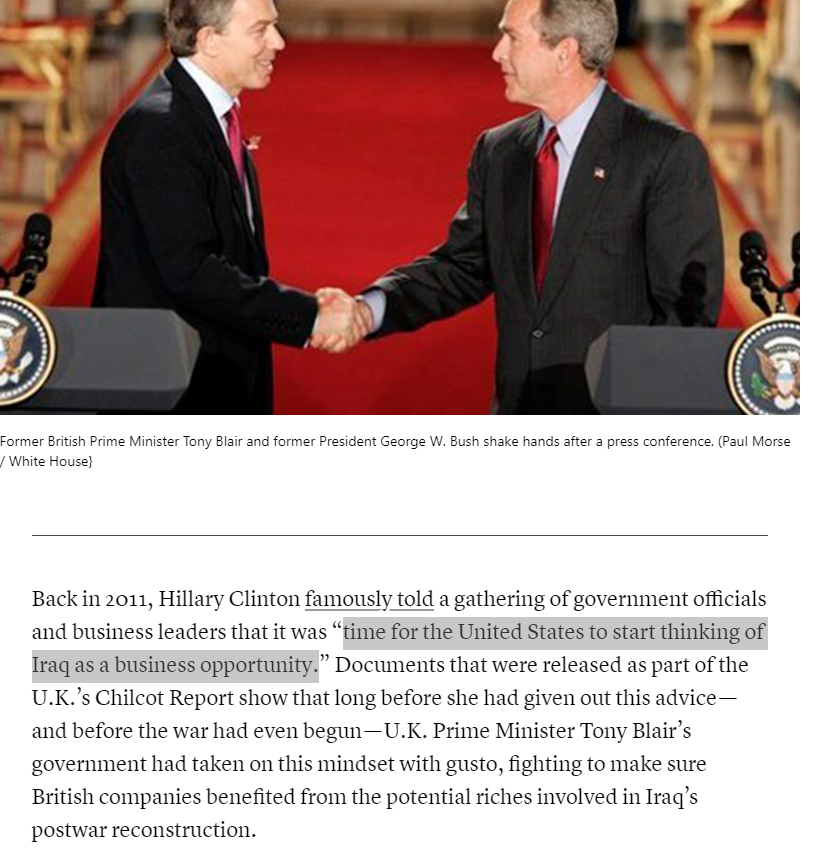

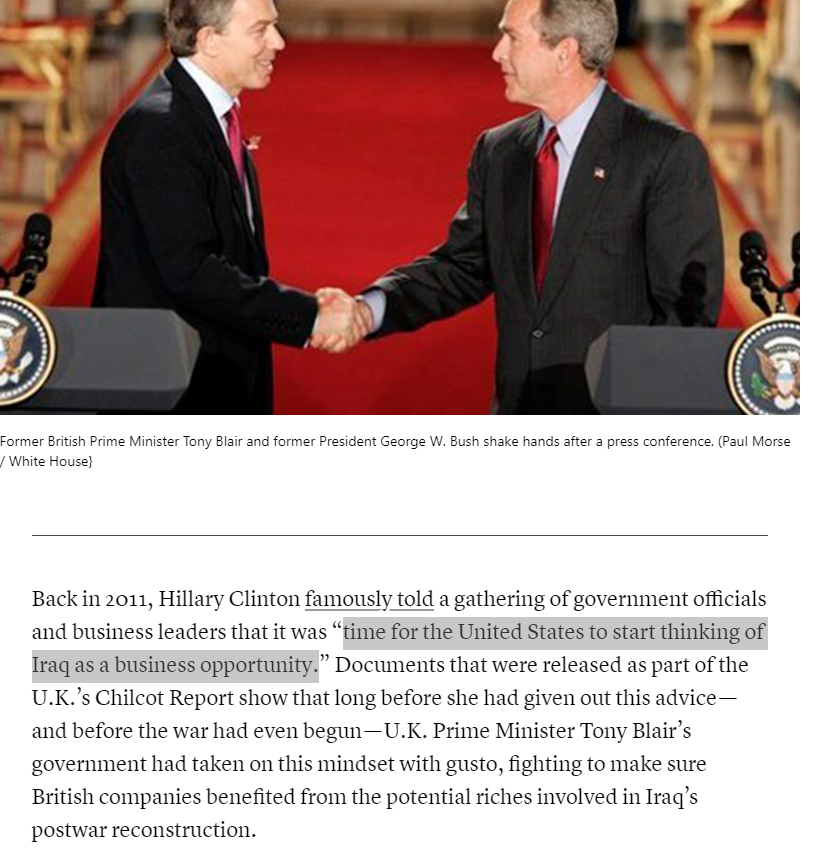

The profit motive behind war has ancient roots, but the contemporary industrialization of war’s financial benefits is a disturbing testament to our time. In the context of the Iraq War, companies like Halliburton thrived because of their adeptness in infrastructure and logistics and because former executives held key government positions. This revolving door of politics and private business isn’t new but requires sharp scrutiny.

In the digital age, it’s easier to disseminate narratives and reveal stark truths about corruption and cronyism. And yet, the systemic issues that allow such exploitation to occur persist. How does a world-yielding tragedy translate to lucrative opportunities for a select few, and what does this pattern say about the integrity of our socio-political systems?

Halliburton’s Financial Windfall from Conflict

Halliburton’s involvement in the Iraq War represents a quintessential example of how corporations can profiteer from conflict. Initially, the company secured contracts worth billions to provide logistical support and rebuild infrastructure, a situation made possible by its close ties to political figures, namely former CEO Dick Cheney, who served as Vice President of the United States during the Iraq War. The contracts, often granted without competitive bidding, covered various services, from constructing military bases to restoring oil fields.

Critics argue that Halliburton’s success in obtaining these contracts was significantly aided by its intimate relationship with the government, highlighting a concerning overlap between corporate interests and public policy. The scrutiny intensified as reports surfaced of overcharging and mismanagement of funds. Despite these allegations, Halliburton’s revenue from these projects was substantial, stoking debates about the ethics of profit-making in wartime and the mechanisms to prevent conflict of interest and ensure accountability in public contracts. This situation underscores the complexity of war profiteering in the modern era, where the intertwining of corporate prowess and political influence can skew public policy towards the interests of the few, often at the expense of the many.

Thanks to the war in Iraq, Dick Cheney is worth over 90 million dollars.

Halliburton’s $40 Billion Decade

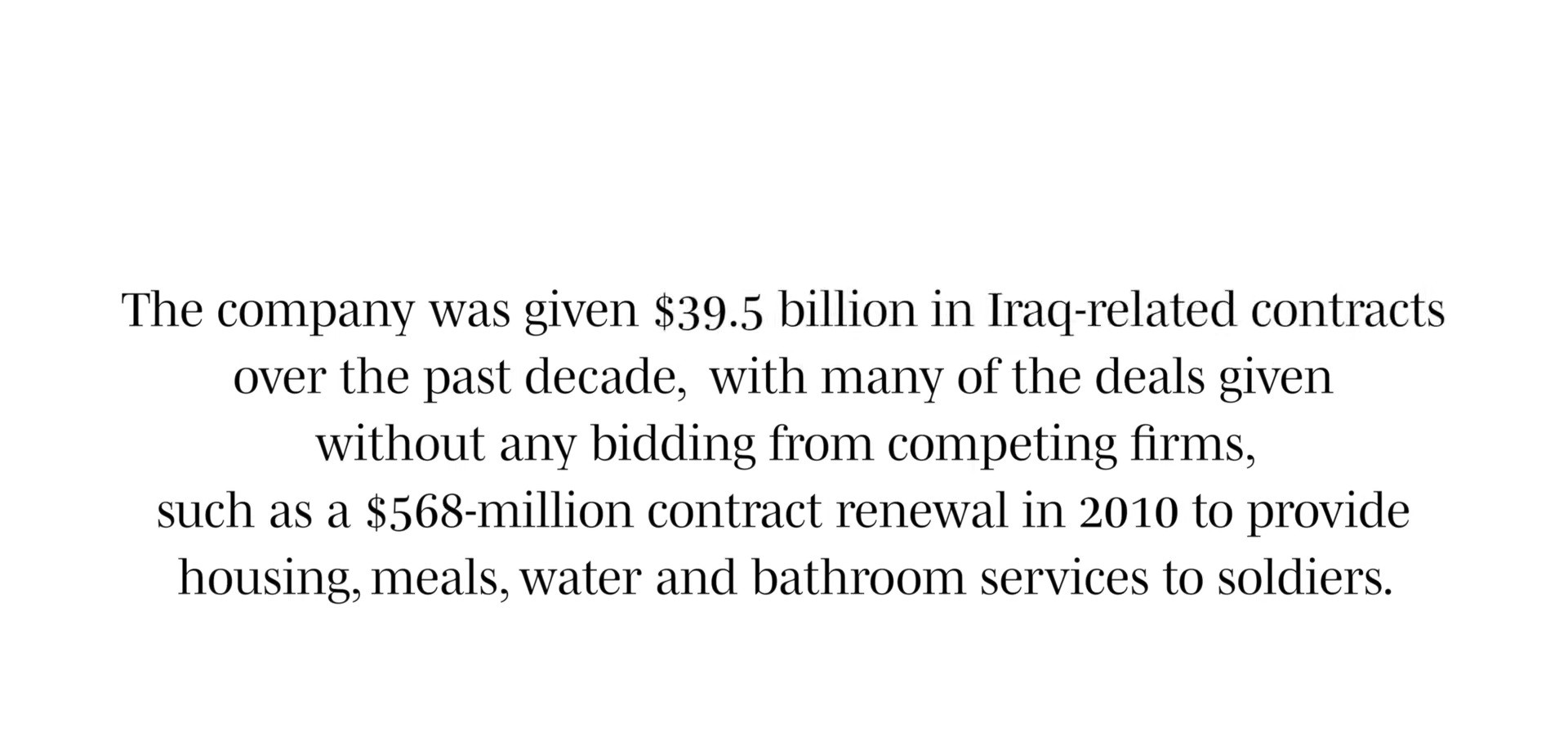

Halliburton’s financial success over ten years, particularly through its involvement in conflict zones, underscores a broader narrative of war profiteering. From 2003 to 2013, during the height and aftermath of the Iraq War, Halliburton’s revenue streams burgeoned, with the company reportedly making over $40 billion. This financial boon was primarily the result of lucrative government contracts for rebuilding efforts and logistical support in Iraq and Afghanistan. The ability of Halliburton to secure such contracts, often with little to no competitive bidding, was facilitated by its deep entrenchment within the political sphere, bolstered by former executives holding positions of significant governmental power.

This period marked a significant spike in Halliburton’s profit margins and a shift in public and political scrutiny toward the ethics of such earnings amidst conflict. The company’s adeptness at navigating the complex landscape of government contracting underlines a dual reality: the essential role that private firms play in supporting military and reconstruction efforts and the profound questions it raises about the transparency and accountability of such engagements. Halliburton’s $40 billion Decade is a testament to the intertwined fates of corporate enterprise and foreign policy, a relationship that, while immensely profitable for some, demands rigorous oversight to align with ethical governance and public service principles.

Halliburton’s Supply Chain Dominance in Military Support

Halliburton’s expansive role in supporting American troops extends beyond infrastructure and logistics, including the critical supply of food and essentials. This contract further cements its status as a key player in military operations abroad. Leveraging its logistical expertise and established relationships within the government, Halliburton was awarded contracts to provide comprehensive support services, including food, water, shelter, and sanitation for soldiers stationed in conflict zones.

Awarding these contracts, often with limited competitive bidding, ignited debates over the company’s influence on government procurement processes and raised questions about potential conflicts of interest given Halliburton’s deep political ties.

The company’s ability to secure such contracts is emblematic of its strategic positioning at the intersection of corporate capability and political access. Critics point to the lack of transparency and oversight in the bidding process, concerns amplified by subsequent allegations of overcharging and service shortfalls. However, supporters argue that Halliburton’s capacity to meet military personnel’s vast and varied needs in challenging environments justifies its predominant role in military logistics and supply chains.

This aspect of Halliburton’s operations—feeding and supplying troops—highlights the blurred lines between military necessity and corporate profit. This dynamic underscores the complexities of modern warfare, where private firms have become indispensable to executing military strategies. The debate over Halliburton’s contracts for supplying American troops thus encapsulates broader concerns about the privatization of war, the accountability of contractors, and the ethics of profit-making from military engagements.

Transitioning Focus: From Defense to Reconstruction

As the dust of conflict begins to settle and war fervor cools down, a notable shift occurs in prioritizing contracts from defense to reconstruction. This transition marks a lucrative phase for corporations like Halliburton, which adeptly moved their focus from supplying military operations to leading the charge in rebuilding war-torn regions. The end of active combat does not signify a reduction in opportunities for these corporations; rather, it opens a new chapter where the emphasis on reconstruction provides a continuous stream of contracts, often with the same lack of competitive bidding that characterized their defense contracts.

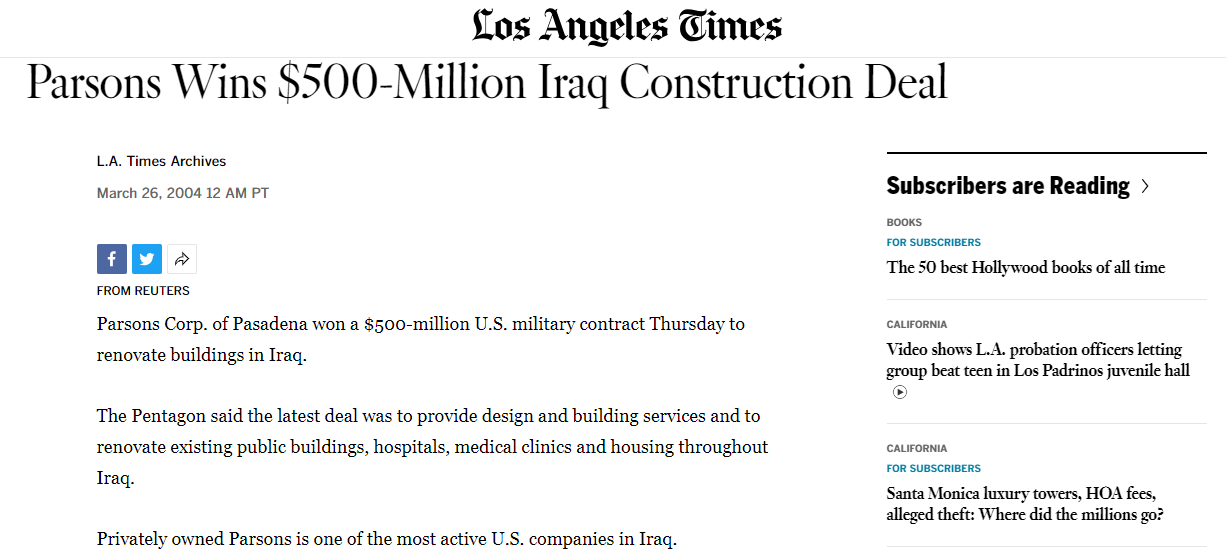

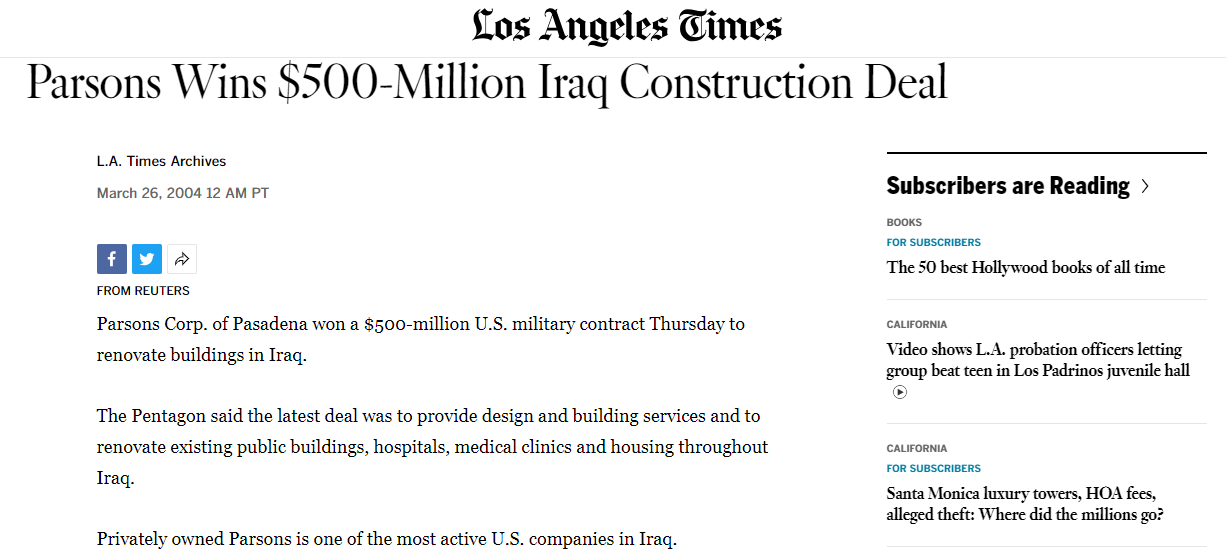

Parsons and Bechtel’s Gains from Reconstruction Efforts

Following in the footsteps of companies like Halliburton, Parsons, and Bechtel, they also significantly benefited from the reconstruction efforts in post-conflict areas, particularly Iraq and Afghanistan. These benefits stemmed largely from the substantial contracts they awarded for rebuilding critical infrastructure—from roads and bridges to schools and government buildings. With backgrounds in engineering and construction, both companies were well-positioned to undertake the massive rebuilding projects essential for restoring normalcy in war-torn regions.

The lack of competitive bidding, a common theme in the awarding of reconstruction contracts during this period, played a pivotal role in the financial gains of Parsons and Bechtel. Their historical involvement in large-scale projects and established relationships with governments ensured they were among the first considered when contracts were distributed. This situation highlighted their dominance in the sector and raised questions about the fairness and transparency of the contract-awarding process.

Financially, the rewards were significant, with both companies reporting increased revenues as a direct result of their involvement in these reconstruction projects. However, Halliburton, Parsons, and Bechtel faced scrutiny over the efficacy of their work and the ethical implications of profiting from post-conflict reconstruction, underscoring the ongoing debate around the privatization of reconstruction efforts and the role of large corporations in shaping post-conflict outcomes.

The True Cost of War

The cost of war transcends the tangible and plummets deep into the intangible, measured not solely in the expenditure of billions of dollars but profoundly in the lives lost, families irreparably torn apart, and the lingering generational trauma that follows. Yet, amidst this grim tally, another numerical figure is often glossed over—the war dividend reaped by the privileged few. Companies like Bechtel, deeply entrenched in the fabric of conflict, stand as stark emblems of a disturbing symbiosis between certain enterprises and the perpetuation of violence.

Beyond the immediate physical destruction and loss, wars dismantle social structures, disrupt economies, and leave deep psychological scars on survivors. They reshape the geography of entire regions, not just physically but socio-politically, often setting the stage for future conflicts. The environmental damage is profound, too, with the ravages of war leaving landscapes scarred and ecosystems disrupted for generations.

In the shadow of these catastrophic impacts, the narrative of economic benefits is frequently spun, framed as support for troops or safeguarding national security interests. However, it’s critical to challenge this rhetoric and ask the hard questions. Are the true beneficiaries of war the brave men and women serving on the front lines, defending ideals and territories, or are they the invisible hands—corporate moguls, defense contractors, and the corridors of power—guiding the war machine for their gain?

This complex web of interests highlights the need for a deeper examination of the motives behind wars and their true cost to humanity. It underscores the importance of striving for peace and questioning the motives of those who profit from the perpetuation of conflict.

The Controversy of Cost-Plus Contracts

The use of cost-plus contracts by the United States, particularly in war, has been a subject ripe for controversy. These contracts guarantee the reimbursement of a company’s expenses plus an additional profit margin, providing a financial safety net for contractors but raising significant concerns about spending efficiency and accountability. In the milieu of conflict, where the urgency and scale of operations can escalate rapidly, cost-plus contracts have facilitated an environment where overspending is not just a risk but a reality.

Critics argue that such contracts remove the incentive for companies to control costs, potentially leading to inflated expenses that the government, and ultimately the taxpayers, must bear. The situation becomes even more complicated when these contracts are awarded in the shadow of war, when oversight may be diminished due to the immediacy of military needs and the classified nature of many defense-related activities. The controversies surrounding Halliburton’s contracts in Iraq, often cited as examples of cost-plus arrangements gone awry, underscore the potential for misuse and the challenge of balancing operational expedience with fiscal responsibility.

While designed to encourage companies to take on the unpredictable challenges associated with war zones, this contracting model prompts a broader debate about the oversight and accountability mechanisms necessary to prevent abuse. It raises the question of whether the financial assurances offered by cost-plus contracts align too closely with the interests of contractors at the expense of public interest and ethical governance in times of conflict.

Holding the Purse Strings and the Consciences

The notion of a “just war” has been contorted when those wielding the swords are aligned with financial stakeholders benefitting from the swing of the battle axe. When businessmen-turned-politicians make decisions with their wallets as much in mind as the welfare of their citizenry, the very foundation of democracy faces erosion.

As a society at large, we must ask ourselves what type of conflict we stand to inherit if the lure of a war-driven economy further dismantles the mechanisms of oversight, transparency, and public accountability mechanisms. The checks and balances that should apply to our financial engagements in international politics seem particularly obscure when world economies are shaped not for the people but for the pockets of the elite.

The Path to Profiting from Conflict: A Strategic Overview for Greedy Politicians (Satire)

In summary, to carve a lucrative path from wartime engagements, the initial step is to secure the alliance of former politicians—recruit, rather lavishly compensate them with high salaries, stock options, and bonuses, regardless of their business acumen. This establishes an indispensable network of influence and access.

To capitalize on the actual conflict phase, your business model should encompass constructing military bases, provisioning the troops, ensuring their comfort with amenities like air conditioning, and supplying weaponry—all while leveraging cost-plus contracts to inflate expenses as feasibly as possible. This approach guarantees immediate returns and sets the stage for the next phase of profit maximization.

As the conflict reaches its zenith, pivoting towards the reconstruction discourse is critical, positioning oneself advantageously to clinch those early deals. The reconstruction phase often predicates on the war-impacted nation incurring debt from Western financiers to afford your services, perpetuating a cycle of dependency and profit for your enterprise.

This approach, as exemplified by Halliburton’s enduring presence and profit in Iraq, underscores the model of ‘financial slavery.’

By following these outlined steps, you position yourself to not just benefit in the short term but to establish a lasting legacy of profit across various sectors—from oil fracking to construction and beyond—mirroring Halliburton’s decades-long enrichment from its initial projects in Iraq.

A Call to Action

Merely acknowledging this unsettling arrangement is not enough. We must call for institutional reform and a renewed commitment to ethical stewardship in war and peace, especially as we wade through the volatile waters of global crises. We, the global citizens, must push back against the normalization of profiteering from conflict and demand that our elected officials and corporate entities answer the higher call of moral obligation over financial allurement.

The inexorable interconnection between war and wealth is a tale as old as civilization itself. But in our modern, interconnected world, where the fates of nations are intertwined, and every decision bears global repercussions, it is time to reexamine our tolerance for the perverse enrichment spun from a world entrenched in conflict. Our voices, our vote, and our vigilance can stem the tide of a disastrous slide into the arms of those who would craft our world wars not with the pen of necessity but with the ink of personal advantage. It is time to rewrite the narrative, charting a course where war is not a canvas for financial supremacy but a dialogue for reconciliation and peace.

Relevant Satire Illustrations

The Dark Art of War Profiteering

War profiteering, often regarded as a shadowy and immoral enterprise, thrives on the despair and destruction wrought by conflicts around the world. This dark art is not a product of modern warfare but a timeless phenomenon, with historical roots tracing back to when the first empires were built on conquest and subjugation.

In contemporary settings, the mechanisms of war profiteering have evolved, leveraging advanced technology, global financial systems, and intricate legal structures to maximize profits. The vested interests of corporations and individuals in prolonging conflicts for financial gain present a grave moral dilemma. It raises profound ethical questions about the role of profit in the context of human suffering and the integrity of those who stand to gain from the perpetuation of violence.

War isn’t just a geopolitical conflict. For many, it’s a lucrative business, saddeningly ushered by people who should protect the common interest. The deep financial involvement of influential companies like Halliburton, Parsons, and Bechtel in the Iraq War is a drop in the vast ocean of machinations on the global warfare stage.

In this article, I’ll explore how the elite profit from world conflicts and why we, as a society, must question and challenge this unethical underbelly of global crises.

Capitalizing on Calamity

The profit motive behind war has ancient roots, but the contemporary industrialization of war’s financial benefits is a disturbing testament to our time. In the context of the Iraq War, companies like Halliburton thrived because of their adeptness in infrastructure and logistics and because former executives held key government positions. This revolving door of politics and private business isn’t new but requires sharp scrutiny.

In the digital age, it’s easier to disseminate narratives and reveal stark truths about corruption and cronyism. And yet, the systemic issues that allow such exploitation to occur persist. How does a world-yielding tragedy translate to lucrative opportunities for a select few, and what does this pattern say about the integrity of our socio-political systems?

Halliburton’s Financial Windfall from Conflict

Halliburton’s involvement in the Iraq War represents a quintessential example of how corporations can profiteer from conflict. Initially, the company secured contracts worth billions to provide logistical support and rebuild infrastructure, a situation made possible by its close ties to political figures, namely former CEO Dick Cheney, who served as Vice President of the United States during the Iraq War. The contracts, often granted without competitive bidding, covered various services, from constructing military bases to restoring oil fields.

Critics argue that Halliburton’s success in obtaining these contracts was significantly aided by its intimate relationship with the government, highlighting a concerning overlap between corporate interests and public policy. The scrutiny intensified as reports surfaced of overcharging and mismanagement of funds. Despite these allegations, Halliburton’s revenue from these projects was substantial, stoking debates about the ethics of profit-making in wartime and the mechanisms to prevent conflict of interest and ensure accountability in public contracts. This situation underscores the complexity of war profiteering in the modern era, where the intertwining of corporate prowess and political influence can skew public policy towards the interests of the few, often at the expense of the many.

Thanks to the war in Iraq, Dick Cheney is worth over 90 million dollars.

Halliburton’s $40 Billion Decade

Halliburton’s financial success over ten years, particularly through its involvement in conflict zones, underscores a broader narrative of war profiteering. From 2003 to 2013, during the height and aftermath of the Iraq War, Halliburton’s revenue streams burgeoned, with the company reportedly making over $40 billion. This financial boon was primarily the result of lucrative government contracts for rebuilding efforts and logistical support in Iraq and Afghanistan. The ability of Halliburton to secure such contracts, often with little to no competitive bidding, was facilitated by its deep entrenchment within the political sphere, bolstered by former executives holding positions of significant governmental power.

This period marked a significant spike in Halliburton’s profit margins and a shift in public and political scrutiny toward the ethics of such earnings amidst conflict. The company’s adeptness at navigating the complex landscape of government contracting underlines a dual reality: the essential role that private firms play in supporting military and reconstruction efforts and the profound questions it raises about the transparency and accountability of such engagements. Halliburton’s $40 billion Decade is a testament to the intertwined fates of corporate enterprise and foreign policy, a relationship that, while immensely profitable for some, demands rigorous oversight to align with ethical governance and public service principles.

Halliburton’s Supply Chain Dominance in Military Support

Halliburton’s expansive role in supporting American troops extends beyond infrastructure and logistics, including the critical supply of food and essentials. This contract further cements its status as a key player in military operations abroad. Leveraging its logistical expertise and established relationships within the government, Halliburton was awarded contracts to provide comprehensive support services, including food, water, shelter, and sanitation for soldiers stationed in conflict zones.

Awarding these contracts, often with limited competitive bidding, ignited debates over the company’s influence on government procurement processes and raised questions about potential conflicts of interest given Halliburton’s deep political ties.

The company’s ability to secure such contracts is emblematic of its strategic positioning at the intersection of corporate capability and political access. Critics point to the lack of transparency and oversight in the bidding process, concerns amplified by subsequent allegations of overcharging and service shortfalls. However, supporters argue that Halliburton’s capacity to meet military personnel’s vast and varied needs in challenging environments justifies its predominant role in military logistics and supply chains.

This aspect of Halliburton’s operations—feeding and supplying troops—highlights the blurred lines between military necessity and corporate profit. This dynamic underscores the complexities of modern warfare, where private firms have become indispensable to executing military strategies. The debate over Halliburton’s contracts for supplying American troops thus encapsulates broader concerns about the privatization of war, the accountability of contractors, and the ethics of profit-making from military engagements.

Transitioning Focus: From Defense to Reconstruction

As the dust of conflict begins to settle and war fervor cools down, a notable shift occurs in prioritizing contracts from defense to reconstruction. This transition marks a lucrative phase for corporations like Halliburton, which adeptly moved their focus from supplying military operations to leading the charge in rebuilding war-torn regions. The end of active combat does not signify a reduction in opportunities for these corporations; rather, it opens a new chapter where the emphasis on reconstruction provides a continuous stream of contracts, often with the same lack of competitive bidding that characterized their defense contracts.

Parsons and Bechtel’s Gains from Reconstruction Efforts

Following in the footsteps of companies like Halliburton, Parsons, and Bechtel, they also significantly benefited from the reconstruction efforts in post-conflict areas, particularly Iraq and Afghanistan. These benefits stemmed largely from the substantial contracts they awarded for rebuilding critical infrastructure—from roads and bridges to schools and government buildings. With backgrounds in engineering and construction, both companies were well-positioned to undertake the massive rebuilding projects essential for restoring normalcy in war-torn regions.

The lack of competitive bidding, a common theme in the awarding of reconstruction contracts during this period, played a pivotal role in the financial gains of Parsons and Bechtel. Their historical involvement in large-scale projects and established relationships with governments ensured they were among the first considered when contracts were distributed. This situation highlighted their dominance in the sector and raised questions about the fairness and transparency of the contract-awarding process.

Financially, the rewards were significant, with both companies reporting increased revenues as a direct result of their involvement in these reconstruction projects. However, Halliburton, Parsons, and Bechtel faced scrutiny over the efficacy of their work and the ethical implications of profiting from post-conflict reconstruction, underscoring the ongoing debate around the privatization of reconstruction efforts and the role of large corporations in shaping post-conflict outcomes.

The True Cost of War

The cost of war transcends the tangible and plummets deep into the intangible, measured not solely in the expenditure of billions of dollars but profoundly in the lives lost, families irreparably torn apart, and the lingering generational trauma that follows. Yet, amidst this grim tally, another numerical figure is often glossed over—the war dividend reaped by the privileged few. Companies like Bechtel, deeply entrenched in the fabric of conflict, stand as stark emblems of a disturbing symbiosis between certain enterprises and the perpetuation of violence.

Beyond the immediate physical destruction and loss, wars dismantle social structures, disrupt economies, and leave deep psychological scars on survivors. They reshape the geography of entire regions, not just physically but socio-politically, often setting the stage for future conflicts. The environmental damage is profound, too, with the ravages of war leaving landscapes scarred and ecosystems disrupted for generations.

In the shadow of these catastrophic impacts, the narrative of economic benefits is frequently spun, framed as support for troops or safeguarding national security interests. However, it’s critical to challenge this rhetoric and ask the hard questions. Are the true beneficiaries of war the brave men and women serving on the front lines, defending ideals and territories, or are they the invisible hands—corporate moguls, defense contractors, and the corridors of power—guiding the war machine for their gain?

This complex web of interests highlights the need for a deeper examination of the motives behind wars and their true cost to humanity. It underscores the importance of striving for peace and questioning the motives of those who profit from the perpetuation of conflict.

The Controversy of Cost-Plus Contracts

The use of cost-plus contracts by the United States, particularly in war, has been a subject ripe for controversy. These contracts guarantee the reimbursement of a company’s expenses plus an additional profit margin, providing a financial safety net for contractors but raising significant concerns about spending efficiency and accountability. In the milieu of conflict, where the urgency and scale of operations can escalate rapidly, cost-plus contracts have facilitated an environment where overspending is not just a risk but a reality.

Critics argue that such contracts remove the incentive for companies to control costs, potentially leading to inflated expenses that the government, and ultimately the taxpayers, must bear. The situation becomes even more complicated when these contracts are awarded in the shadow of war, when oversight may be diminished due to the immediacy of military needs and the classified nature of many defense-related activities. The controversies surrounding Halliburton’s contracts in Iraq, often cited as examples of cost-plus arrangements gone awry, underscore the potential for misuse and the challenge of balancing operational expedience with fiscal responsibility.

While designed to encourage companies to take on the unpredictable challenges associated with war zones, this contracting model prompts a broader debate about the oversight and accountability mechanisms necessary to prevent abuse. It raises the question of whether the financial assurances offered by cost-plus contracts align too closely with the interests of contractors at the expense of public interest and ethical governance in times of conflict.

Holding the Purse Strings and the Consciences

The notion of a “just war” has been contorted when those wielding the swords are aligned with financial stakeholders benefitting from the swing of the battle axe. When businessmen-turned-politicians make decisions with their wallets as much in mind as the welfare of their citizenry, the very foundation of democracy faces erosion.

As a society at large, we must ask ourselves what type of conflict we stand to inherit if the lure of a war-driven economy further dismantles the mechanisms of oversight, transparency, and public accountability mechanisms. The checks and balances that should apply to our financial engagements in international politics seem particularly obscure when world economies are shaped not for the people but for the pockets of the elite.

The Path to Profiting from Conflict: A Strategic Overview for Greedy Politicians (Satire)

In summary, to carve a lucrative path from wartime engagements, the initial step is to secure the alliance of former politicians—recruit, rather lavishly compensate them with high salaries, stock options, and bonuses, regardless of their business acumen. This establishes an indispensable network of influence and access.

To capitalize on the actual conflict phase, your business model should encompass constructing military bases, provisioning the troops, ensuring their comfort with amenities like air conditioning, and supplying weaponry—all while leveraging cost-plus contracts to inflate expenses as feasibly as possible. This approach guarantees immediate returns and sets the stage for the next phase of profit maximization.

As the conflict reaches its zenith, pivoting towards the reconstruction discourse is critical, positioning oneself advantageously to clinch those early deals. The reconstruction phase often predicates on the war-impacted nation incurring debt from Western financiers to afford your services, perpetuating a cycle of dependency and profit for your enterprise.

This approach, as exemplified by Halliburton’s enduring presence and profit in Iraq, underscores the model of ‘financial slavery.’

By following these outlined steps, you position yourself to not just benefit in the short term but to establish a lasting legacy of profit across various sectors—from oil fracking to construction and beyond—mirroring Halliburton’s decades-long enrichment from its initial projects in Iraq.

A Call to Action

Merely acknowledging this unsettling arrangement is not enough. We must call for institutional reform and a renewed commitment to ethical stewardship in war and peace, especially as we wade through the volatile waters of global crises. We, the global citizens, must push back against the normalization of profiteering from conflict and demand that our elected officials and corporate entities answer the higher call of moral obligation over financial allurement.

The inexorable interconnection between war and wealth is a tale as old as civilization itself. But in our modern, interconnected world, where the fates of nations are intertwined, and every decision bears global repercussions, it is time to reexamine our tolerance for the perverse enrichment spun from a world entrenched in conflict. Our voices, our vote, and our vigilance can stem the tide of a disastrous slide into the arms of those who would craft our world wars not with the pen of necessity but with the ink of personal advantage. It is time to rewrite the narrative, charting a course where war is not a canvas for financial supremacy but a dialogue for reconciliation and peace.

Relevant Satire Illustrations

Leave A Comment

Table of content

- The Dark Art of War Profiteering

- Capitalizing on Calamity

- Halliburton’s Financial Windfall from Conflict

- Transitioning Focus: From Defense to Reconstruction

- The True Cost of War

- The Controversy of Cost-Plus Contracts

- Holding the Purse Strings and the Consciences

- The Path to Profiting from Conflict: A Strategic Overview for Greedy Politicians (Satire)

- A Call to Action

- Relevant Satire Illustrations