Palestine, a crossroads of civilizations, religions, and empires, boasts a rich tapestry of cultures and histories that date back four millennia. The region, nestled along the eastern Mediterranean between modern-day Lebanon and Egypt, has always thrived as a multicultural, multiethnic, and multireligious area of the world. It has seen the rise and fall of empires, the spread of religions, and the ebb and flow of different ethnicities, all contributing to its complex historical fabric.

In the 19th century, however, this uninterrupted continuity of history faced an unprecedented challenge. A group of white European colonists, known as Zionists, aimed to establish a Jewish state within the region. This marked the beginning of a systematic drive to displace Palestine’s indigenous people and supplant them with European settlers, a process that ignited the long-standing Arab-Israeli conflict.

While the politics surrounding this conflict may stir controversy, this article seeks to present an evidence-based, historical perspective. We believe that understanding the past is crucial for navigating the path to a brighter future and rectifying historical injustices.

This exploration of the 4,000-year-old history of Palestine is an attempt to illuminate the complexities of this region’s past and present, far removed from the oversimplified narratives that often dominate public discourse.

The Philistines and Ancient Palestine

Dating back to the Late Bronze Age, approximately 3,200 years ago, the roots of Palestine can be traced. This understanding has been reinforced and reshaped by multiple archaeological discoveries that often challenge prevailing views of history. One such groundbreaking discovery took place in 2017 when a 3,000-year-old Philistine graveyard was unearthed near modern-day Ashkelon in western Israel. While the existence of the Philistines in current-day Palestine and Israel is widely recognized, the discovery of the graveyard was an extraordinary revelation. It effectively challenged the Israeli theory that the Philistines were invading pirates from the Aegean Sea. Five inscriptions found at the graveyard reading “Peleset,” an early written form of “Palestine,” provided compelling evidence that the Philistines were indigenous to the region.

The name Philistines gradually evolved into “Palestinians.” Further proof of the existence of indigenous Philistines is found in ancient texts such as an Egyptian scroll dating back to the same era as the 3,000-year-old graveyard. The text mentions the Philistines as one of the neighboring peoples the Egyptians battled. The mere existence of this text contradicts the biblical Canaanite narrative that has been propagated since the nineteenth century by Zionists claiming the region of Palestine. While Canaan indisputably existed as a region, historical evidence reveals that “Canaan” is a biblical term referring to Phoenicia, a civilization corresponding to modern-day Lebanon. Interestingly, this term was only utilized to describe the region for a brief period around 1300 BC.

South of Phoenicia was a region known as Philistia, which after the eighth and seventh centuries BC, was used to designate the entire southern Levantine region, corresponding to modern Israel, Palestine, and even southern Lebanon in later periods. This region ceased being referred to by ancient names such as Canaan and came to be known as Philistia.

The Philistines, as we entered the Iron Age in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, had built a sophisticated urban civilization in this region. Renowned for their advanced shipbuilding techniques, they also demonstrated artistic finesse through the pottery, metalwork, and ivory carvings that have been uncovered in archaeological excavations throughout historic Palestine. During this era, many ancient Palestinian cities came into existence, such as Ghazzah, ‘Asgalan, and Isdud — known today as Gaza, Ashkelon, and Ashdod. However, it’s noteworthy that the original Palestinian inhabitants of Ashkelon and Ashdod were expelled by Israel in 1948.

With their city-states resembling those found in ancient Greek civilization, the Philistines established extensive trade networks with Egypt, Phoenicia, and Arabia. These activities not only sustained the economy of ancient Palestine but also encouraged a multicultural and polytheistic society.

Palestine under Greek and Roman Rule

As time passed, ancient Palestine continued to flourish under Greek and Roman rule. By the fifth century BC, the modern cognate of Philistia – Palestina in Greek, and Palestine in Latin – started to dominate as the name of the region lying between modern-day Lebanon and Egypt. This nomenclature persisted for the next 1,200 years, until the Islamic conquest in 637 AD. Prominent Greek philosopher Aristotle, in his detailed treatises, used this term in the fourth century BC. Herodotus, often referred to as the “Father of History,” portrayed fifth-century BC Palestine as a polytheistic, trade-rich region. The Arabs residing in the southern port cities of Palestine controlled the frankincense trade route extending to India. This granted Palestine considerable wealth and status, along with eastern spices and luxury goods.

Under Roman rule, specifically from 135 to 390 AD, the region was known as Syria Palaestina. Written records from this era reveal the multicultural nature of Palestine, where Christianity was practiced by Arabic, Greek, and Aramaic speakers. However, Greek and Aramaic speakers were also adherents of Judaism, and the region was home to Greek and Latin-speaking polytheists who worshipped an array of gods.

As the history of Roman Palestine unfolded, the region’s name gradually transitioned from Syria Palaestina to simply Palestine. This is evident in the literature of the time, particularly in the works of Greco-Jewish philosopher Philo and Roman geographer Pomponius Mela. Pomponius, writing in 43 AD, described the geography of the region in detail, even mentioning the Arabs of Palestine and the “mighty city” of Gaza.

During the Roman period, Palestine’s infrastructure and urbanization expanded, reflecting its importance to the Roman administration. Interestingly, the name “Jerusalem” was nearly forgotten during this epoch. Following the Hellenistic tradition of renaming cities, Emperor Hadrian gave Jerusalem the new name “Aelia Capitolina”, with “Aelia” being Hadrian’s second name and “Capitolina” referencing the chief god in the Roman pantheon of deities. Records from Palestinian Arabs reveal that they adopted the Arabized name “Iliya” for the city well before the Islamic conquest. Even into the tenth century, the term was still used alongside a new Arabic name for the city — “Bayt al-Maqdis,” or “the Holy City.” This reflects the deep historical roots and multicultural history of Palestine, enriched and shaped by various civilizations over the millennia.

Byzantine Palestine and the Ascendancy of Christianity and Arabs

The Byzantine era marked a significant shift in Palestine’s history, characterized by the rise of Christianity and the increasing influence of Arabs in power. The birthplace of Jesus of Nazareth, Palestine found renewed significance when Christianity was adopted as the state religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century. The region was then divided into three administrative regions by the Christian Byzantine Roman Empire: Palestina Prima, Palestina Secunda, and Palestina Salutaris reflecting the Christian Trinity concept and corresponding to present-day central, northern, and southern Palestine, respectively.

These divisions did not imply complete separation, as the unity among these regions continued culturally, religiously, and politically until the Muslim era in the seventh century. Collectively known as Greater Palestine, the region became globally renowned for its bustling cities, spectacular architecture, sizable population, philosophical centers, and extensive libraries.

By some estimates, Palestine was home to up to 1.5 million residents during the Byzantine period. Around 100,000 of these inhabitants lived in Caesarea Maritima, the cosmopolitan capital of Palestina Prima, which hosted a vibrant mix of Greeks, Arabic and Aramaic-speaking Christians, Jews, Samaritans, and even polytheistic Arabs.

Prominent early Christian philosophical figures, such as Origen, resided in this city in the third century and played instrumental roles in establishing the Library of Caesarea. With a collection of 30,000 manuscripts at its peak, this library was second in size only to the Library of Alexandria in Egypt, making Caesarea one of the most important cities of Classical Antiquity.

The culture of philosophic inquiry and learning permeated throughout Palestinian society, with basic education, spanning Greek, Latin, rhetoric, law, and philosophy, widely accessible, even in villages. This education aimed at producing able administrators and leaders for church and state structures.

The Byzantine era also witnessed an expansion of Palestine’s Arab population. Archaeological evidence suggests the presence of Arabs in Palestine 500 years before the birth of Jesus. By the early third century, the Arab population had grown with the influx of Christian Arabs migrating from Yemen, located on the Arabian Peninsula’s southern coast. These Arabs’ descendants would rule over Palaestina Secunda and Tertia, centuries before the advent of Islam in the seventh century.

The Muslim Conquest and the Flourishing of Palestine

In 637 AD, the Muslim conquest sparked a transformation in Palestine, leading to significant prosperity, further Arabization, and Islamization. The Arabic language, following this conquest, became the primary language of the region, a status it has maintained for over 1,300 years. The region adopted its modern Arabic name, Filastin, which is derived from the ancient Philistia. Alongside Dimashq or Damascus, Filastin constituted a core province of the burgeoning Muslim empire, also known as the “Caliphate.”

The process of Islamization unfolded simultaneously with the spread of Arabic. Arabization was not a new concept, with the Christian Arab population of Palestine expanding and acquiring political power over several centuries. Both Islamization and Arabization were accepted without significant resistance by locals, as the linguistic shift from Aramaic to the closely related Arabic was fairly smooth. Similarly, given that Islam shared its monotheistic roots with Christianity and Judaism, conversions to Islam typically faced less conflict than those in polytheistic regions conquered by Muslim armies.

This peaceful transition was facilitated by the new Muslim rulers’ policy of religious and cultural tolerance towards Palestine’s Christian and Jewish residents. Under Muslim rule, Palestine underwent a period of intense urbanization, with Jerusalem emerging as the epicenter. The holy city was revered as the third most sacred place in Islam, after Mecca and Medina, prompting the construction of grand religious monuments such as the still-standing Dome of the Rock in 691 AD.

The allure of Jerusalem was so profound that Muslim rulers contemplated designating it as the capital of their empire, over Damascus. Contrary to some narratives portraying early Muslim Palestine as a region in decline, historical records present a different story. Palestine’s economy thrived during this era, outstripping any previous benchmarks. According to the tax records of the early Caliphate, Palestine was the wealthiest region in the Levant. Palestinian exports of olive oil, wine, soap, and glassware (crafted by Arab Jews) found eager markets throughout the Mediterranean and even in Europe.

This period of Muslim rule ushered in a “Golden Age” for Palestine, transforming it into a technologically and culturally advanced region. When European crusaders invaded in 1099, they were taken aback by the sophistication of Palestinian society, which markedly surpassed the development levels of their native European towns and cities.

After the European Crusaders were removed, the Ayyubid and Mamluk dynasties governed Palestine.

After the European Crusaders had swept through Palestine from 1147 onwards, aiming to establish Christian supremacy over the Holy Land, it was the legendary military commander Salah al-Din who reversed these conquests at the Battle of Hittin in 1187, reestablishing Muslim rule that would endure for the next seven centuries. However, despite Salah al-Din’s victories, he was unable to recapture the well-fortified coastal city of Acre, which was under the control of French crusaders. His descendants, however, were successful, in liberating Acre from oppressive crusader rule in 1291.

With the restoration of Muslim rule in Palestine, Jews and Muslims were once more able to worship freely without persecution, and religious sites that had been desecrated were restored to their former glory. The Ayyubids, once in power, instituted crucial administrative changes in Palestine. The most notable of these was the designation of Jerusalem as the capital city, a status it would retain for the next 700 years.

Crusaders continued to raid Palestine’s coastal cities, sparking a decline in these areas and an ascendance of inland cities like Jerusalem. Ayyubid rulers, to prevent Crusaders from utilizing their devastating siege techniques in the future, made a radical decision: to tear down the walls of the major cities, hence preventing future sieges.

This drastic decision proved to be ingenious. Jerusalem, remarkably for the medieval period, grew beyond its former walls as a major city without fortifications. This status was consolidated by a period of peace ushered in by the Mamluk dynasty, which came to power in Palestine following the defeat of the Mongolian invaders in 1260. The ensuing tranquil political environment led to Jerusalem becoming a significant city of pilgrimage.

This was facilitated by the Mamluks’ construction of large bathhouses and the provision of clean running water, both essential elements for cities of pilgrimage at the time. One such bathhouse, the Hammam al-Ayn, persists to this day. Jerusalem, along with other inland Palestinian cities, underwent a renaissance of construction during the Mamluk era. The city’s renowned white stone architecture blossomed, much of which is still visible today.

Palestinian Autonomy under Dhaher al-Umar al-Zaydani

The transition from Mamluk to Ottoman rule in 1517 marked a significant moment in Palestine’s history, as the region remained predominantly Muslim and Arabic-speaking while being recognized globally as situated between Egypt and Lebanon. This acknowledgment was not limited only to the indigenous Palestinians; the term ‘Palestine’ was used widely by European cartographers into the 20th century, and even finds a mention in the works of Shakespeare.

The Ottoman period was pivotal for Palestinian history, marking the first instance of Palestinians forming their own state and establishing an identity as a nation. Contrary to the conventional representation of Palestinian nationalism as a product of 19th-century European influence and Ottoman reforms, a deeper historical analysis reveals an earlier emergence of Palestinian statehood.

In fact, the inception of the Palestinian state predates the conventional historical narrative by an entire century. The first Palestinian state was born not from the whims of the elite but rather as a result of a popular uprising against oppressive forces. During the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire was showing signs of decline, leading to an upsurge of discontent among Palestinians in the Galilee region. A charismatic leader emerged in the person of Dhaher al-Umar al-Zaydani, now regarded as a father of modern Palestine.

Throughout the 1720s and 1730s, al-Umar, with an army composed of Christian and Muslim peasants, repeatedly triumphed over the Ottoman forces, eventually establishing an autonomous state within the borders of Palestine. By 1768, the Ottoman officials, humiliated, recognized his victory. While Palestine formally remained an Ottoman frontier territory, it functioned as a de facto sovereign state.

Under al-Umar’s leadership and with popular support from the peasantry, Palestine transformed into an economic powerhouse throughout the latter part of the 18th century. The boom in the Palestinian cotton industry, driven by demand from industrializing countries like France and England, led to a shift towards international trade with Europe. This prosperity allowed Palestine to escape the economic neglect experienced by other parts of the Ottoman Empire, and a fair taxation system was established to fund the self-governed state. Urban development projects changed entire landscapes, with Haifa, for instance, transitioning from a small village to a bustling metropolis within decades.

This era of autonomous Palestinian statehood, beginning in the 1720s, continued until al-Umar died in 1775. While conventional historians often cite the British Mandate of Palestine, established after World War I, as the first instance of Palestinian self-rule, this interpretation overlooks the five-decade-long leadership of al-Umar, which truly signifies the first moment of an autonomous Palestinian state.

The emergence of modern Palestinian nationalism can be traced back to the early nineteenth century, gaining momentum alongside the rise of Zionism.

As the 19th century unfolded, a wave of nationalism swept across Palestine, coinciding with the inception of Zionism. Napoleon Bonaparte, the newly crowned Emperor of France, was aggressively expanding his empire across Europe and North Africa, which included a significant campaign in Egypt and Palestine. However, he met his match in Palestine’s coastal city of Acre, where an Anglo-Ottoman alliance successfully thwarted his advances in 1799, marking the genesis of British colonial interest in Palestine.

Over the subsequent decades, a steady stream of British evangelicals journeyed to the region, helped by travel agencies like Thomas Cook, which started offering organized tours of Palestine. In 1871, an official British delegation arrived with the specific purpose of mapping Palestine, a clear indication of the British intent to stake a claim in the region, especially with the Ottoman Empire on the brink of collapse. The British envisioned Palestine as a tactical outpost en route to British India.

The British Palestine Exploration Fund, co-managed by biblical scholars with evangelical leanings towards the region, was established. Notably, one of its founders, Charles Warren, was an evangelical Christian Zionist and believed in the necessity of a Jewish state in Palestine to expedite the Second Coming of Christ.

Simultaneously, Palestinian nationalism was gaining momentum, predating the emergence of Zionism by nearly fifty years. At the dawn of the 20th century, Palestine was predominantly Muslim and Christian Arab, with a mostly-Arab Jewish minority. Peaceful coexistence marked the relationship between the different religious groups in Palestine until the arrival of European Jews in the late 19th century.

The tides of nationalism were felt by Palestinians of all religious beliefs, expedited by the industrial printing revolution and the spread of secular education. The resultant rise in literacy rates led to a heightened sense of Palestinian nationalism, as publications like “Falastin” became widely circulated by the early 20th century. The choice of the local Palestinian Arabic pronunciation “Falastin” for the newspaper’s name, over the traditional Arabic “Filistin” or “Filastin”, underscores the significance of Palestinian national identity. The newspaper evolved into a vital platform for anti-imperialist sentiments.

Finally, as World War I was drawing to a close, Britain realized its century-old ambition. With the Ottomans on the precipice of defeat, the British army occupied Palestine. Consequently, the League of Nations entrusted the governance of the newly established British Mandate of Palestine to Britain.

The Zionist project was rooted in European settler colonialism and racism.

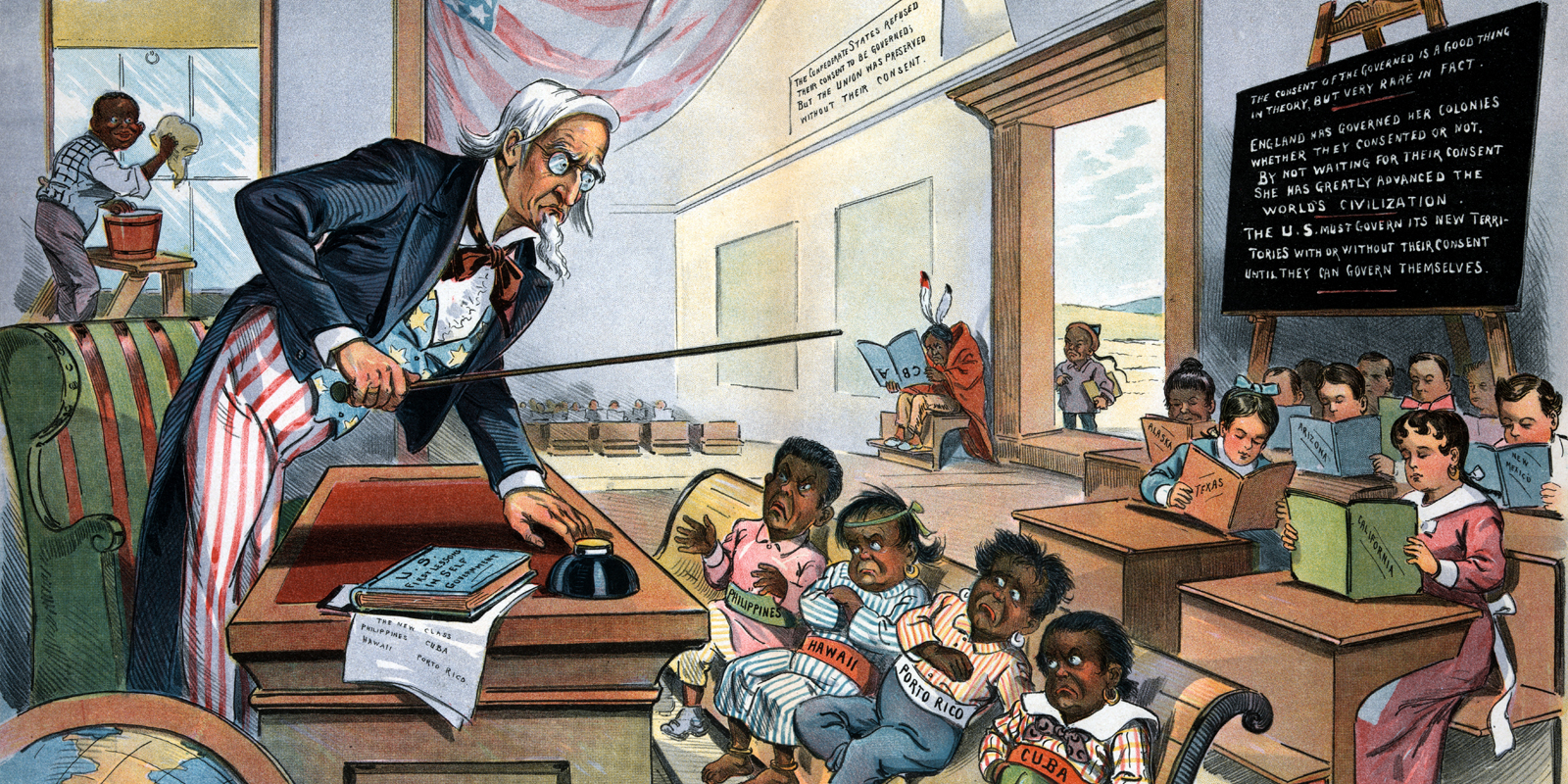

The Zionist project, like other forms of 19th-century European colonialism, was steeped in notions of racial superiority and the overriding priority of European interests. Zionists, much like British colonialists in India, viewed the indigenous Palestinian population as uncivilized and unworthy of self-governance. However, the Zionist agenda differed from many other forms of colonialism in that it was a settler-colonial endeavor, not solely an economic one. The goal was to supplant the indigenous Palestinian population with non-Palestinian Jews.

The narrative propagated by many 19th-century Zionists, that Palestine was a “land without a people for a people without a land,” was not an observation about Palestine’s demographics, but a reflection of the dehumanizing colonial mindset which failed to recognize the existence and rights of the indigenous population. In their pursuit of a Jewish state, Zionist Jews found indispensable allies in British Christian Zionists. Key political figures, including future Prime Minister David Lloyd George, subscribed to the Zionist ideology.

The convergence of British geopolitical interest in Palestine and Zionist lobbying culminated in the 1917 Balfour Declaration. This marked Britain’s official endorsement of the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Before the declaration, Zionist attitudes towards the native Palestinians varied from indifference to racist superiority. However, the intensification of Palestinian anti-Zionism following the British Mandate led the Zionist leadership to a grim conclusion: their vision of a Jewish state could only be realized through the forced displacement of the Palestinians.

Consequently, the creation of an ethnically homogeneous white Jewish colony in the Middle East was pursued with vigor, culminating in the 1948 establishment of the State of Israel. The ancient Palestinian city of Jaffa provides a poignant example of this process. In a series of events now known as the “Nakba,” or catastrophe, Zionist militants expelled the city’s Muslim and Christian Arab inhabitants, replacing them with white European settlers.

The Destruction of Palestinian History by Israel is Widespread and Well-Documented

The deliberate erasure of Palestinian history by the state of Israel is extensive and well-documented. Notably, Jaffa wasn’t the only city subjected to the removal of its original inhabitants. The process started in 1948, with the birth of the state of Israel, which subsequently initiated a systematic campaign of eradicating any historical evidence of Palestine from their newly seized territories. Now in command of the majority of historic Palestine, the Zionists embarked on a strategic process of branding Zionism as the repatriation of indigenous people to their ancestral homeland after a gap of 2,000 years. The Government Names Committee, a newly established entity, played a crucial role in this endeavor.

The committee was set up by David Grün, a Polish Zionist, and the first Prime Minister of Israel. He altered his family name from Grün to the more biblical-sounding “Ben-Gurion.” Most top-ranking Israelis followed suit within the initial years of Israel’s existence. However, merely altering surnames was not enough – the Zionists required a language to facilitate the creation of their country, leading to the invention of Modern Hebrew in the late nineteenth century.

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (formerly Lazar Perelman), the creator of Modern Hebrew, heavily appropriated Palestinian Arabic words, sounds, and grammar for this novel language, integrating numerous words from European languages such as Yiddish and Polish. Post the 1948 Nakba, Zionists had control over 80 percent of historic Palestine, displacing most of the original inhabitants. The Arab inhabitants of Palestine, numbering around 700,000, were now refugees, removed from their ancestral homeland.

Despite this, Palestinians exemplified remarkable resilience under these conditions. Facing replacement by a settler population and obliteration from history, Palestinian culture continues to prosper. Over the recent decades, a wealth of novels, films, archives, websites, and other repositories of Palestinian identity have been created and are now widely propagated throughout Palestinian civil society. Much of this cultural identity is deeply rooted in Palestinian nationalist sentiment from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The author hopes for a shift in this focus, with Palestinian educational institutions extending their attention beyond the long and diverse history of Palestine. After all, modern Palestinian Arabs are the descendants of a rich amalgamation of various peoples – Arabs, Greeks, Canaanites, Philistines, and many others.

Summary

The designation “Palestine” has been the predominant term used for marking the geographical region nestled between Egypt and Lebanon along the Mediterranean coast, a usage tracing back 3,200 years. Historically, this region has been a vibrant melting pot of diverse cultures, languages, and religions. The Palestinian Arabs of today are the genetic tapestry of a variety of groups that have populated the region over millennia, including Greeks, Philistines, Israelites, Arabs, Romans, and others. Islam has been the predominating religion for the past 1,400 years, though Christianity and Judaism have also been practiced continuously by the indigenous population for thousands of years. However, the continuous existence of the Palestinian people was interrupted by Zionism, a European colonial project aspiring to lay claim to Palestine as its territory. This endeavor led to the depopulation of Palestinian cities and the appropriation of their culture and language.

Palestine, a crossroads of civilizations, religions, and empires, boasts a rich tapestry of cultures and histories that date back four millennia. The region, nestled along the eastern Mediterranean between modern-day Lebanon and Egypt, has always thrived as a multicultural, multiethnic, and multireligious area of the world. It has seen the rise and fall of empires, the spread of religions, and the ebb and flow of different ethnicities, all contributing to its complex historical fabric.

In the 19th century, however, this uninterrupted continuity of history faced an unprecedented challenge. A group of white European colonists, known as Zionists, aimed to establish a Jewish state within the region. This marked the beginning of a systematic drive to displace Palestine’s indigenous people and supplant them with European settlers, a process that ignited the long-standing Arab-Israeli conflict.

While the politics surrounding this conflict may stir controversy, this article seeks to present an evidence-based, historical perspective. We believe that understanding the past is crucial for navigating the path to a brighter future and rectifying historical injustices.

This exploration of the 4,000-year-old history of Palestine is an attempt to illuminate the complexities of this region’s past and present, far removed from the oversimplified narratives that often dominate public discourse.

The Philistines and Ancient Palestine

Dating back to the Late Bronze Age, approximately 3,200 years ago, the roots of Palestine can be traced. This understanding has been reinforced and reshaped by multiple archaeological discoveries that often challenge prevailing views of history. One such groundbreaking discovery took place in 2017 when a 3,000-year-old Philistine graveyard was unearthed near modern-day Ashkelon in western Israel. While the existence of the Philistines in current-day Palestine and Israel is widely recognized, the discovery of the graveyard was an extraordinary revelation. It effectively challenged the Israeli theory that the Philistines were invading pirates from the Aegean Sea. Five inscriptions found at the graveyard reading “Peleset,” an early written form of “Palestine,” provided compelling evidence that the Philistines were indigenous to the region.

The name Philistines gradually evolved into “Palestinians.” Further proof of the existence of indigenous Philistines is found in ancient texts such as an Egyptian scroll dating back to the same era as the 3,000-year-old graveyard. The text mentions the Philistines as one of the neighboring peoples the Egyptians battled. The mere existence of this text contradicts the biblical Canaanite narrative that has been propagated since the nineteenth century by Zionists claiming the region of Palestine. While Canaan indisputably existed as a region, historical evidence reveals that “Canaan” is a biblical term referring to Phoenicia, a civilization corresponding to modern-day Lebanon. Interestingly, this term was only utilized to describe the region for a brief period around 1300 BC.

South of Phoenicia was a region known as Philistia, which after the eighth and seventh centuries BC, was used to designate the entire southern Levantine region, corresponding to modern Israel, Palestine, and even southern Lebanon in later periods. This region ceased being referred to by ancient names such as Canaan and came to be known as Philistia.

The Philistines, as we entered the Iron Age in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, had built a sophisticated urban civilization in this region. Renowned for their advanced shipbuilding techniques, they also demonstrated artistic finesse through the pottery, metalwork, and ivory carvings that have been uncovered in archaeological excavations throughout historic Palestine. During this era, many ancient Palestinian cities came into existence, such as Ghazzah, ‘Asgalan, and Isdud — known today as Gaza, Ashkelon, and Ashdod. However, it’s noteworthy that the original Palestinian inhabitants of Ashkelon and Ashdod were expelled by Israel in 1948.

With their city-states resembling those found in ancient Greek civilization, the Philistines established extensive trade networks with Egypt, Phoenicia, and Arabia. These activities not only sustained the economy of ancient Palestine but also encouraged a multicultural and polytheistic society.

Palestine under Greek and Roman Rule

As time passed, ancient Palestine continued to flourish under Greek and Roman rule. By the fifth century BC, the modern cognate of Philistia – Palestina in Greek, and Palestine in Latin – started to dominate as the name of the region lying between modern-day Lebanon and Egypt. This nomenclature persisted for the next 1,200 years, until the Islamic conquest in 637 AD. Prominent Greek philosopher Aristotle, in his detailed treatises, used this term in the fourth century BC. Herodotus, often referred to as the “Father of History,” portrayed fifth-century BC Palestine as a polytheistic, trade-rich region. The Arabs residing in the southern port cities of Palestine controlled the frankincense trade route extending to India. This granted Palestine considerable wealth and status, along with eastern spices and luxury goods.

Under Roman rule, specifically from 135 to 390 AD, the region was known as Syria Palaestina. Written records from this era reveal the multicultural nature of Palestine, where Christianity was practiced by Arabic, Greek, and Aramaic speakers. However, Greek and Aramaic speakers were also adherents of Judaism, and the region was home to Greek and Latin-speaking polytheists who worshipped an array of gods.

As the history of Roman Palestine unfolded, the region’s name gradually transitioned from Syria Palaestina to simply Palestine. This is evident in the literature of the time, particularly in the works of Greco-Jewish philosopher Philo and Roman geographer Pomponius Mela. Pomponius, writing in 43 AD, described the geography of the region in detail, even mentioning the Arabs of Palestine and the “mighty city” of Gaza.

During the Roman period, Palestine’s infrastructure and urbanization expanded, reflecting its importance to the Roman administration. Interestingly, the name “Jerusalem” was nearly forgotten during this epoch. Following the Hellenistic tradition of renaming cities, Emperor Hadrian gave Jerusalem the new name “Aelia Capitolina”, with “Aelia” being Hadrian’s second name and “Capitolina” referencing the chief god in the Roman pantheon of deities. Records from Palestinian Arabs reveal that they adopted the Arabized name “Iliya” for the city well before the Islamic conquest. Even into the tenth century, the term was still used alongside a new Arabic name for the city — “Bayt al-Maqdis,” or “the Holy City.” This reflects the deep historical roots and multicultural history of Palestine, enriched and shaped by various civilizations over the millennia.

Byzantine Palestine and the Ascendancy of Christianity and Arabs

The Byzantine era marked a significant shift in Palestine’s history, characterized by the rise of Christianity and the increasing influence of Arabs in power. The birthplace of Jesus of Nazareth, Palestine found renewed significance when Christianity was adopted as the state religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century. The region was then divided into three administrative regions by the Christian Byzantine Roman Empire: Palestina Prima, Palestina Secunda, and Palestina Salutaris reflecting the Christian Trinity concept and corresponding to present-day central, northern, and southern Palestine, respectively.

These divisions did not imply complete separation, as the unity among these regions continued culturally, religiously, and politically until the Muslim era in the seventh century. Collectively known as Greater Palestine, the region became globally renowned for its bustling cities, spectacular architecture, sizable population, philosophical centers, and extensive libraries.

By some estimates, Palestine was home to up to 1.5 million residents during the Byzantine period. Around 100,000 of these inhabitants lived in Caesarea Maritima, the cosmopolitan capital of Palestina Prima, which hosted a vibrant mix of Greeks, Arabic and Aramaic-speaking Christians, Jews, Samaritans, and even polytheistic Arabs.

Prominent early Christian philosophical figures, such as Origen, resided in this city in the third century and played instrumental roles in establishing the Library of Caesarea. With a collection of 30,000 manuscripts at its peak, this library was second in size only to the Library of Alexandria in Egypt, making Caesarea one of the most important cities of Classical Antiquity.

The culture of philosophic inquiry and learning permeated throughout Palestinian society, with basic education, spanning Greek, Latin, rhetoric, law, and philosophy, widely accessible, even in villages. This education aimed at producing able administrators and leaders for church and state structures.

The Byzantine era also witnessed an expansion of Palestine’s Arab population. Archaeological evidence suggests the presence of Arabs in Palestine 500 years before the birth of Jesus. By the early third century, the Arab population had grown with the influx of Christian Arabs migrating from Yemen, located on the Arabian Peninsula’s southern coast. These Arabs’ descendants would rule over Palaestina Secunda and Tertia, centuries before the advent of Islam in the seventh century.

The Muslim Conquest and the Flourishing of Palestine

In 637 AD, the Muslim conquest sparked a transformation in Palestine, leading to significant prosperity, further Arabization, and Islamization. The Arabic language, following this conquest, became the primary language of the region, a status it has maintained for over 1,300 years. The region adopted its modern Arabic name, Filastin, which is derived from the ancient Philistia. Alongside Dimashq or Damascus, Filastin constituted a core province of the burgeoning Muslim empire, also known as the “Caliphate.”

The process of Islamization unfolded simultaneously with the spread of Arabic. Arabization was not a new concept, with the Christian Arab population of Palestine expanding and acquiring political power over several centuries. Both Islamization and Arabization were accepted without significant resistance by locals, as the linguistic shift from Aramaic to the closely related Arabic was fairly smooth. Similarly, given that Islam shared its monotheistic roots with Christianity and Judaism, conversions to Islam typically faced less conflict than those in polytheistic regions conquered by Muslim armies.

This peaceful transition was facilitated by the new Muslim rulers’ policy of religious and cultural tolerance towards Palestine’s Christian and Jewish residents. Under Muslim rule, Palestine underwent a period of intense urbanization, with Jerusalem emerging as the epicenter. The holy city was revered as the third most sacred place in Islam, after Mecca and Medina, prompting the construction of grand religious monuments such as the still-standing Dome of the Rock in 691 AD.

The allure of Jerusalem was so profound that Muslim rulers contemplated designating it as the capital of their empire, over Damascus. Contrary to some narratives portraying early Muslim Palestine as a region in decline, historical records present a different story. Palestine’s economy thrived during this era, outstripping any previous benchmarks. According to the tax records of the early Caliphate, Palestine was the wealthiest region in the Levant. Palestinian exports of olive oil, wine, soap, and glassware (crafted by Arab Jews) found eager markets throughout the Mediterranean and even in Europe.

This period of Muslim rule ushered in a “Golden Age” for Palestine, transforming it into a technologically and culturally advanced region. When European crusaders invaded in 1099, they were taken aback by the sophistication of Palestinian society, which markedly surpassed the development levels of their native European towns and cities.

After the European Crusaders were removed, the Ayyubid and Mamluk dynasties governed Palestine.

After the European Crusaders had swept through Palestine from 1147 onwards, aiming to establish Christian supremacy over the Holy Land, it was the legendary military commander Salah al-Din who reversed these conquests at the Battle of Hittin in 1187, reestablishing Muslim rule that would endure for the next seven centuries. However, despite Salah al-Din’s victories, he was unable to recapture the well-fortified coastal city of Acre, which was under the control of French crusaders. His descendants, however, were successful, in liberating Acre from oppressive crusader rule in 1291.

With the restoration of Muslim rule in Palestine, Jews and Muslims were once more able to worship freely without persecution, and religious sites that had been desecrated were restored to their former glory. The Ayyubids, once in power, instituted crucial administrative changes in Palestine. The most notable of these was the designation of Jerusalem as the capital city, a status it would retain for the next 700 years.

Crusaders continued to raid Palestine’s coastal cities, sparking a decline in these areas and an ascendance of inland cities like Jerusalem. Ayyubid rulers, to prevent Crusaders from utilizing their devastating siege techniques in the future, made a radical decision: to tear down the walls of the major cities, hence preventing future sieges.

This drastic decision proved to be ingenious. Jerusalem, remarkably for the medieval period, grew beyond its former walls as a major city without fortifications. This status was consolidated by a period of peace ushered in by the Mamluk dynasty, which came to power in Palestine following the defeat of the Mongolian invaders in 1260. The ensuing tranquil political environment led to Jerusalem becoming a significant city of pilgrimage.

This was facilitated by the Mamluks’ construction of large bathhouses and the provision of clean running water, both essential elements for cities of pilgrimage at the time. One such bathhouse, the Hammam al-Ayn, persists to this day. Jerusalem, along with other inland Palestinian cities, underwent a renaissance of construction during the Mamluk era. The city’s renowned white stone architecture blossomed, much of which is still visible today.

Palestinian Autonomy under Dhaher al-Umar al-Zaydani

The transition from Mamluk to Ottoman rule in 1517 marked a significant moment in Palestine’s history, as the region remained predominantly Muslim and Arabic-speaking while being recognized globally as situated between Egypt and Lebanon. This acknowledgment was not limited only to the indigenous Palestinians; the term ‘Palestine’ was used widely by European cartographers into the 20th century, and even finds a mention in the works of Shakespeare.

The Ottoman period was pivotal for Palestinian history, marking the first instance of Palestinians forming their own state and establishing an identity as a nation. Contrary to the conventional representation of Palestinian nationalism as a product of 19th-century European influence and Ottoman reforms, a deeper historical analysis reveals an earlier emergence of Palestinian statehood.

In fact, the inception of the Palestinian state predates the conventional historical narrative by an entire century. The first Palestinian state was born not from the whims of the elite but rather as a result of a popular uprising against oppressive forces. During the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire was showing signs of decline, leading to an upsurge of discontent among Palestinians in the Galilee region. A charismatic leader emerged in the person of Dhaher al-Umar al-Zaydani, now regarded as a father of modern Palestine.

Throughout the 1720s and 1730s, al-Umar, with an army composed of Christian and Muslim peasants, repeatedly triumphed over the Ottoman forces, eventually establishing an autonomous state within the borders of Palestine. By 1768, the Ottoman officials, humiliated, recognized his victory. While Palestine formally remained an Ottoman frontier territory, it functioned as a de facto sovereign state.

Under al-Umar’s leadership and with popular support from the peasantry, Palestine transformed into an economic powerhouse throughout the latter part of the 18th century. The boom in the Palestinian cotton industry, driven by demand from industrializing countries like France and England, led to a shift towards international trade with Europe. This prosperity allowed Palestine to escape the economic neglect experienced by other parts of the Ottoman Empire, and a fair taxation system was established to fund the self-governed state. Urban development projects changed entire landscapes, with Haifa, for instance, transitioning from a small village to a bustling metropolis within decades.

This era of autonomous Palestinian statehood, beginning in the 1720s, continued until al-Umar died in 1775. While conventional historians often cite the British Mandate of Palestine, established after World War I, as the first instance of Palestinian self-rule, this interpretation overlooks the five-decade-long leadership of al-Umar, which truly signifies the first moment of an autonomous Palestinian state.

The emergence of modern Palestinian nationalism can be traced back to the early nineteenth century, gaining momentum alongside the rise of Zionism.

As the 19th century unfolded, a wave of nationalism swept across Palestine, coinciding with the inception of Zionism. Napoleon Bonaparte, the newly crowned Emperor of France, was aggressively expanding his empire across Europe and North Africa, which included a significant campaign in Egypt and Palestine. However, he met his match in Palestine’s coastal city of Acre, where an Anglo-Ottoman alliance successfully thwarted his advances in 1799, marking the genesis of British colonial interest in Palestine.

Over the subsequent decades, a steady stream of British evangelicals journeyed to the region, helped by travel agencies like Thomas Cook, which started offering organized tours of Palestine. In 1871, an official British delegation arrived with the specific purpose of mapping Palestine, a clear indication of the British intent to stake a claim in the region, especially with the Ottoman Empire on the brink of collapse. The British envisioned Palestine as a tactical outpost en route to British India.

The British Palestine Exploration Fund, co-managed by biblical scholars with evangelical leanings towards the region, was established. Notably, one of its founders, Charles Warren, was an evangelical Christian Zionist and believed in the necessity of a Jewish state in Palestine to expedite the Second Coming of Christ.

Simultaneously, Palestinian nationalism was gaining momentum, predating the emergence of Zionism by nearly fifty years. At the dawn of the 20th century, Palestine was predominantly Muslim and Christian Arab, with a mostly-Arab Jewish minority. Peaceful coexistence marked the relationship between the different religious groups in Palestine until the arrival of European Jews in the late 19th century.

The tides of nationalism were felt by Palestinians of all religious beliefs, expedited by the industrial printing revolution and the spread of secular education. The resultant rise in literacy rates led to a heightened sense of Palestinian nationalism, as publications like “Falastin” became widely circulated by the early 20th century. The choice of the local Palestinian Arabic pronunciation “Falastin” for the newspaper’s name, over the traditional Arabic “Filistin” or “Filastin”, underscores the significance of Palestinian national identity. The newspaper evolved into a vital platform for anti-imperialist sentiments.

Finally, as World War I was drawing to a close, Britain realized its century-old ambition. With the Ottomans on the precipice of defeat, the British army occupied Palestine. Consequently, the League of Nations entrusted the governance of the newly established British Mandate of Palestine to Britain.

The Zionist project was rooted in European settler colonialism and racism.

The Zionist project, like other forms of 19th-century European colonialism, was steeped in notions of racial superiority and the overriding priority of European interests. Zionists, much like British colonialists in India, viewed the indigenous Palestinian population as uncivilized and unworthy of self-governance. However, the Zionist agenda differed from many other forms of colonialism in that it was a settler-colonial endeavor, not solely an economic one. The goal was to supplant the indigenous Palestinian population with non-Palestinian Jews.

The narrative propagated by many 19th-century Zionists, that Palestine was a “land without a people for a people without a land,” was not an observation about Palestine’s demographics, but a reflection of the dehumanizing colonial mindset which failed to recognize the existence and rights of the indigenous population. In their pursuit of a Jewish state, Zionist Jews found indispensable allies in British Christian Zionists. Key political figures, including future Prime Minister David Lloyd George, subscribed to the Zionist ideology.

The convergence of British geopolitical interest in Palestine and Zionist lobbying culminated in the 1917 Balfour Declaration. This marked Britain’s official endorsement of the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Before the declaration, Zionist attitudes towards the native Palestinians varied from indifference to racist superiority. However, the intensification of Palestinian anti-Zionism following the British Mandate led the Zionist leadership to a grim conclusion: their vision of a Jewish state could only be realized through the forced displacement of the Palestinians.

Consequently, the creation of an ethnically homogeneous white Jewish colony in the Middle East was pursued with vigor, culminating in the 1948 establishment of the State of Israel. The ancient Palestinian city of Jaffa provides a poignant example of this process. In a series of events now known as the “Nakba,” or catastrophe, Zionist militants expelled the city’s Muslim and Christian Arab inhabitants, replacing them with white European settlers.

The Destruction of Palestinian History by Israel is Widespread and Well-Documented

The deliberate erasure of Palestinian history by the state of Israel is extensive and well-documented. Notably, Jaffa wasn’t the only city subjected to the removal of its original inhabitants. The process started in 1948, with the birth of the state of Israel, which subsequently initiated a systematic campaign of eradicating any historical evidence of Palestine from their newly seized territories. Now in command of the majority of historic Palestine, the Zionists embarked on a strategic process of branding Zionism as the repatriation of indigenous people to their ancestral homeland after a gap of 2,000 years. The Government Names Committee, a newly established entity, played a crucial role in this endeavor.

The committee was set up by David Grün, a Polish Zionist, and the first Prime Minister of Israel. He altered his family name from Grün to the more biblical-sounding “Ben-Gurion.” Most top-ranking Israelis followed suit within the initial years of Israel’s existence. However, merely altering surnames was not enough – the Zionists required a language to facilitate the creation of their country, leading to the invention of Modern Hebrew in the late nineteenth century.

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (formerly Lazar Perelman), the creator of Modern Hebrew, heavily appropriated Palestinian Arabic words, sounds, and grammar for this novel language, integrating numerous words from European languages such as Yiddish and Polish. Post the 1948 Nakba, Zionists had control over 80 percent of historic Palestine, displacing most of the original inhabitants. The Arab inhabitants of Palestine, numbering around 700,000, were now refugees, removed from their ancestral homeland.

Despite this, Palestinians exemplified remarkable resilience under these conditions. Facing replacement by a settler population and obliteration from history, Palestinian culture continues to prosper. Over the recent decades, a wealth of novels, films, archives, websites, and other repositories of Palestinian identity have been created and are now widely propagated throughout Palestinian civil society. Much of this cultural identity is deeply rooted in Palestinian nationalist sentiment from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The author hopes for a shift in this focus, with Palestinian educational institutions extending their attention beyond the long and diverse history of Palestine. After all, modern Palestinian Arabs are the descendants of a rich amalgamation of various peoples – Arabs, Greeks, Canaanites, Philistines, and many others.

Summary

The designation “Palestine” has been the predominant term used for marking the geographical region nestled between Egypt and Lebanon along the Mediterranean coast, a usage tracing back 3,200 years. Historically, this region has been a vibrant melting pot of diverse cultures, languages, and religions. The Palestinian Arabs of today are the genetic tapestry of a variety of groups that have populated the region over millennia, including Greeks, Philistines, Israelites, Arabs, Romans, and others. Islam has been the predominating religion for the past 1,400 years, though Christianity and Judaism have also been practiced continuously by the indigenous population for thousands of years. However, the continuous existence of the Palestinian people was interrupted by Zionism, a European colonial project aspiring to lay claim to Palestine as its territory. This endeavor led to the depopulation of Palestinian cities and the appropriation of their culture and language.

Leave A Comment

Table of content

- The Philistines and Ancient Palestine

- Palestine under Greek and Roman Rule

- Byzantine Palestine and the Ascendancy of Christianity and Arabs

- The Muslim Conquest and the Flourishing of Palestine

- After the European Crusaders were removed, the Ayyubid and Mamluk dynasties governed Palestine.

- Palestinian Autonomy under Dhaher al-Umar al-Zaydani

- The emergence of modern Palestinian nationalism can be traced back to the early nineteenth century, gaining momentum alongside the rise of Zionism.

- The Zionist project was rooted in European settler colonialism and racism.

- The Destruction of Palestinian History by Israel is Widespread and Well-Documented

- Summary