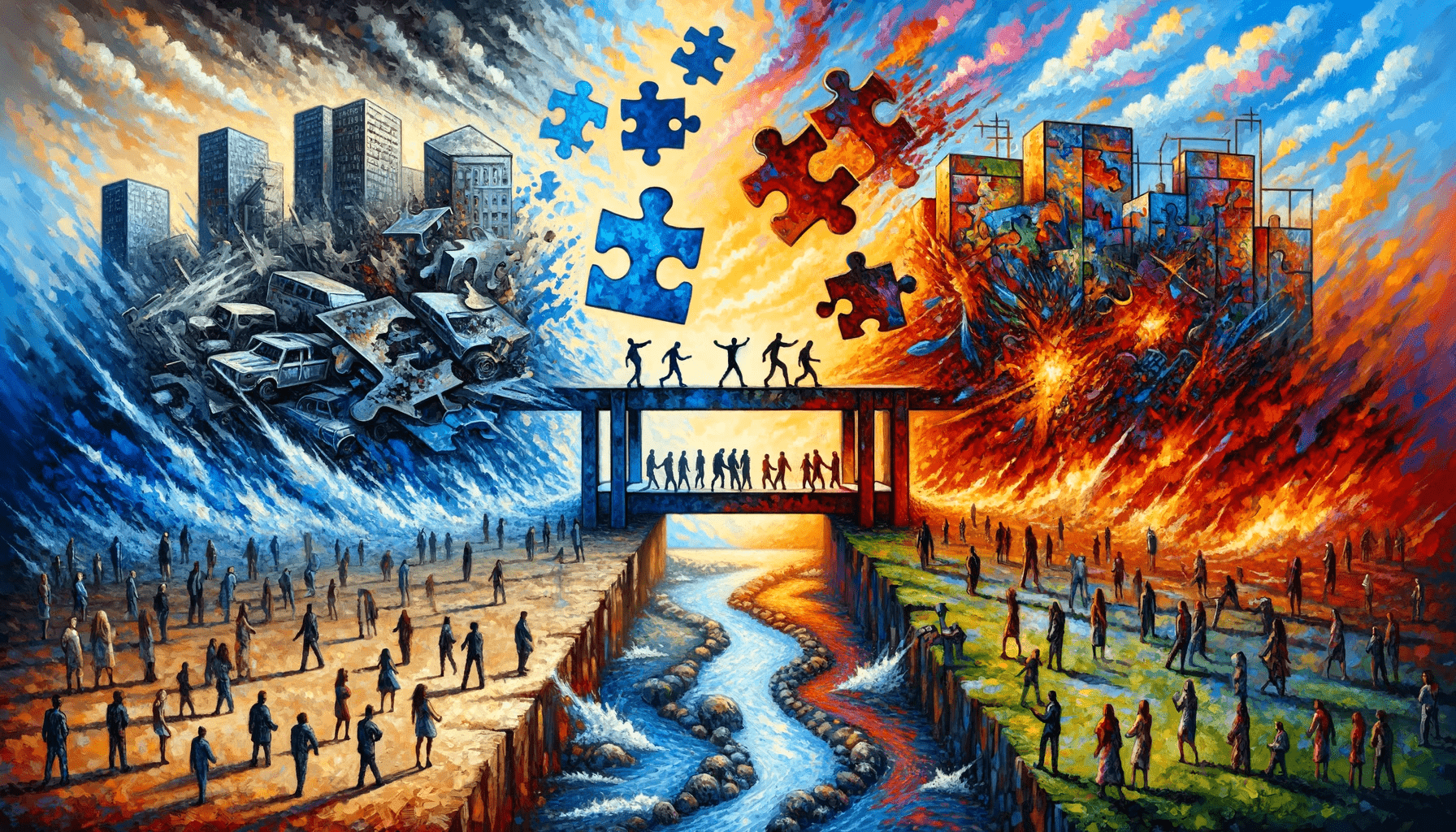

Is our society on the verge of collapsing? Are things getting better or worse?

This brings to light the intriguing paradox of societal perception. While many agree that society is declining, the reasons behind this belief vary greatly depending on one’s political standpoint. Some argue that the erosion of traditional values and structures is the main issue, while others attribute it to social inequality or environmental degradation. This difference in opinion highlights the complexity of societal problems and the challenge of identifying single causes for perceived societal decline.

These divergent views often result in a blame game that further complicates the situation. Each side perceives itself as the solution – the proverbial ‘cure’ to societal woes – while casting the other as the root cause of the problems. This cyclical pattern of blame and counter-blame exacerbates divisions and hampers efforts toward constructive dialogues and solutions. The perception of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ echoes through each aspect of societal debates, underscoring the complexities in addressing multifaceted societal issues.

To assess these societal concerns objectively, it’s essential to delve into credible data sources and analyze them critically. For instance, if we look at the allegations of moral decay, do the crime rates, instances of violence, or other quantifiable factors support this claim? Moreover, as we evaluate the argument that environmental degradation is spurring societal decline, we need to consider scientific studies that examine the impact of climate change on our societies. Similarly, analyzing income distribution statistics can shed light on the claims about growing social inequality. It’s only through careful examination of such empirical evidence that we can ascertain the validity of these narratives and establish a more grounded understanding of societal trends. This data-centric approach may not offer the complete picture, but it adds an essential layer of objectivity to our discussions, offering a solid foundation for productive dialogues and potential solutions.

In the sphere of societal discussions, explanations grounded in empirical evidence often hold more weight than mere narratives. Narratives, though useful in conveying complex ideas and invoking empathy, risk oversimplification of multifaceted societal issues and may be influenced by biases. Conversely, explanations that are founded on data and critical analysis add an element of objectivity, fostering informed dialogues. These explanations provide a more accurate reflection of societal trends and can guide effective policymaking. However, it’s crucial to remember that while data-driven explanations are vital, they must be communicated effectively. The marriage of accurate, objective explanations with compelling narratives can lead to a more nuanced understanding of societal issues and drive meaningful change.

8 Key Questions to Assess Potential Societal Collapse

I have formulated eight questions that I believe serve as reliable indicators of the state of society, regardless of one’s political inclinations. While I intended to select questions that can be answered with measurable data, I acknowledge that some of them may be more ambiguous than others. Nonetheless, I sought to retain the essence of the original meaning while enhancing the overall quality of the writing in terms of word choice, structure, readability, and eloquence.

- Are we dying less?

- Are we living longer?

- Are we more peaceful?

- Are we freer?

- Are we committing fewer crimes?

- Are we more prosperous?

- Are we more knowledgeable?

- Are we happier?

You might instinctively think that you know the answers to these questions, but you may be surprised when confronted with actual data. Our perceptions are often influenced by personal experiences and the media, which may not accurately represent the broader societal trends. It’s important to approach these questions with an open mind, putting aside preconceived notions and biases. Remember, our objective here is not to validate our perspectives but to seek a clearer understanding of the societal landscape. Therefore, we will delve into these questions, armed with curiosity and a willingness to challenge our beliefs.

Are We Dying Less?

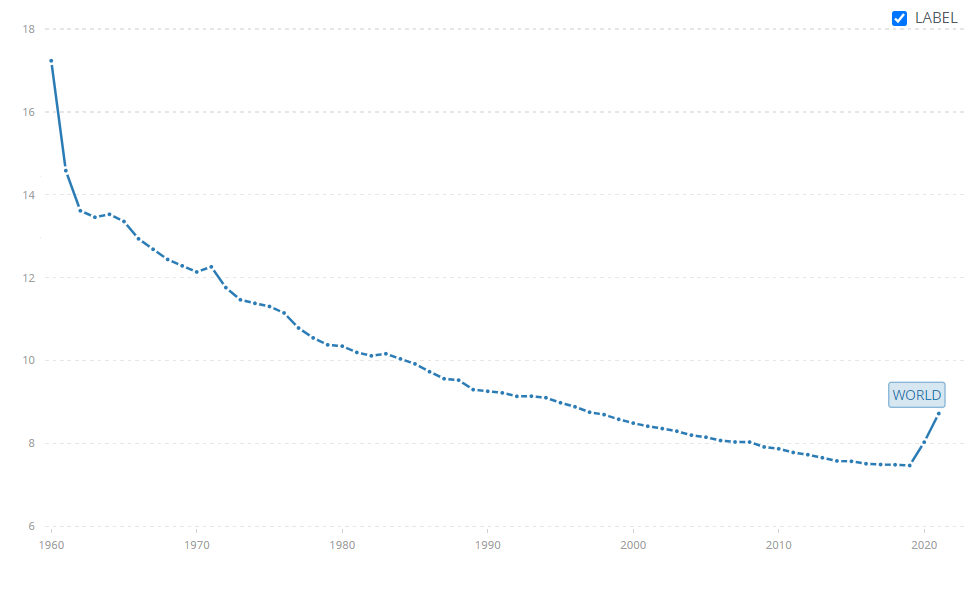

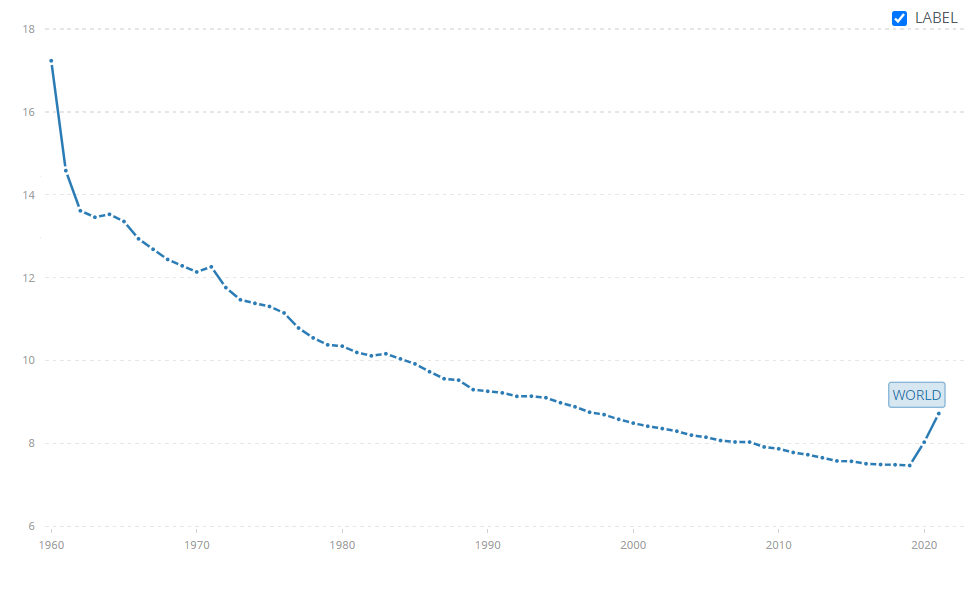

According to the World Bank, worldwide death rates have significantly declined from 1960 to 2020. This statistic, expressed as the number of deaths per 1000 people, provides a good measure of general health and the quality of life across the globe.

In 1960, the global death rate stood at approximately 17.9 deaths per 1000 people. As of 2020, this number has dropped to around 7.6 deaths per 1000 people. This decline in death rate over the past six decades is a testament to numerous factors including advancements in healthcare, improvements in living conditions, and effective public health policies and programs. The data serves as empirical evidence that, in terms of mortality rate, we are certainly faring better now than in the past.

While exact figures from centuries past may not be readily available, various historical records and studies indicate that the death rate was significantly higher than what we observe today. For instance, it’s documented that infectious diseases such as the bubonic plague, Spanish flu, and numerous outbreaks of cholera claimed millions of lives, contributing to a high death rate. Moreover, lack of access to modern healthcare, poor living conditions, and frequent wars also led to increased mortality. Although it’s challenging to extrapolate precise figures from these historical accounts, the consensus among historians and demographers aligns with the notion of a considerably higher death rate in the past. This trend underscores the progress humanity has made over the centuries in enhancing life expectancy and reducing the death rate.

At the turn of the 20th century, the statistics were quite grim. A person had a staggering one in three chance of dying from pneumonia, tuberculosis, or diarrhea. This reality was faced just a little over a hundred years ago. These diseases, which are now largely preventable and treatable due to advancements in healthcare and sanitation, were once considered a death sentence. It’s a somber reflection of the state of public health merely a century ago, highlighting the significant strides we’ve made in improving human health and longevity.

However, it must be noted that not all death rates are created equally. This brings into sharp focus the even grimmer realities of the past. Our ancestors had a significantly lower life expectancy compared to ours today. The fact that people weren’t living as long as they do today fundamentally skews our understanding of historical death rates. The advancements in medical science, sanitation, nutrition, and safety regulations have played pivotal roles in extending the human lifespan. These improvements have not only caused a decline in mortality rates but also have enabled more and more individuals to live into old age.

This leads us to the second question.

Are We Living Longer?

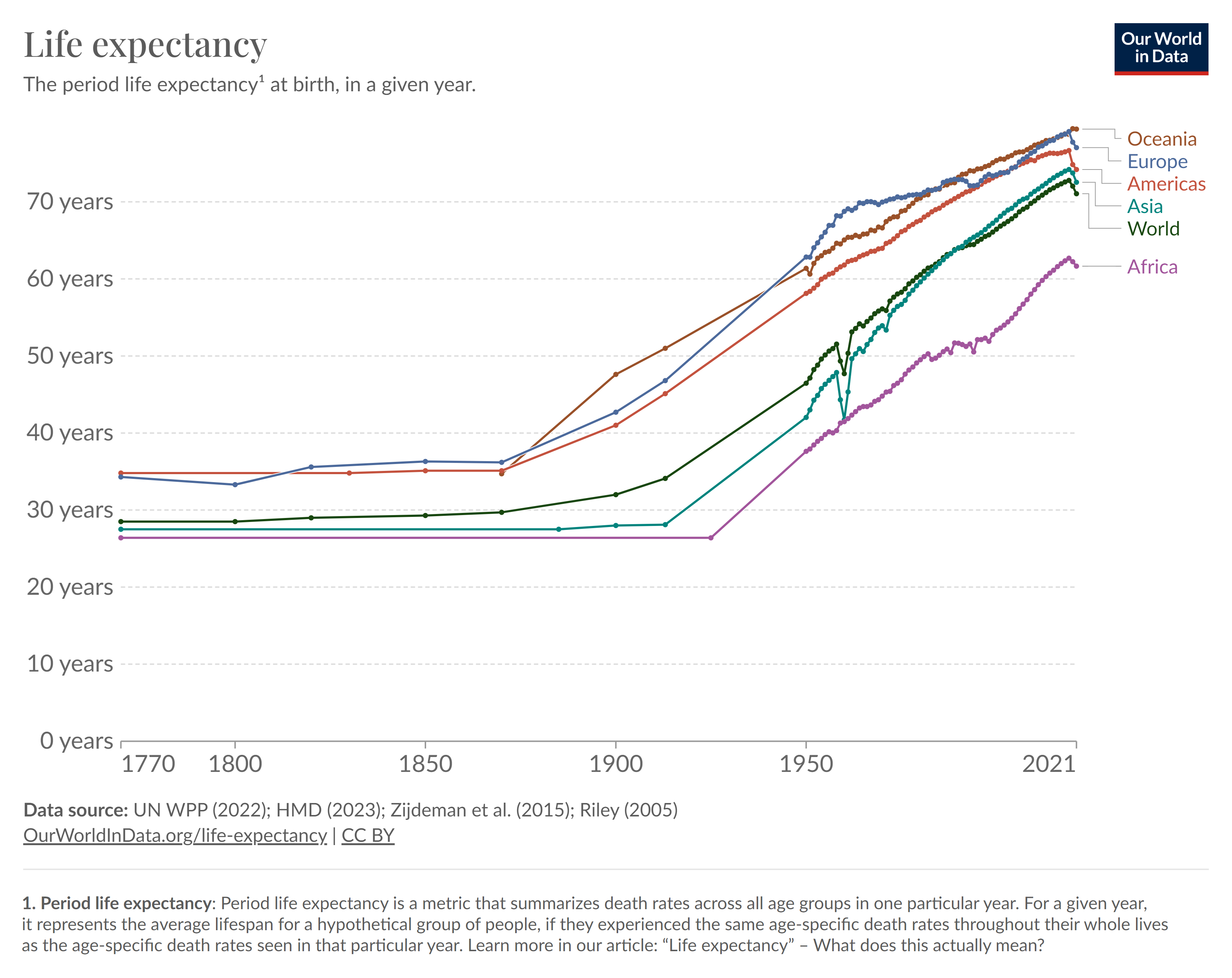

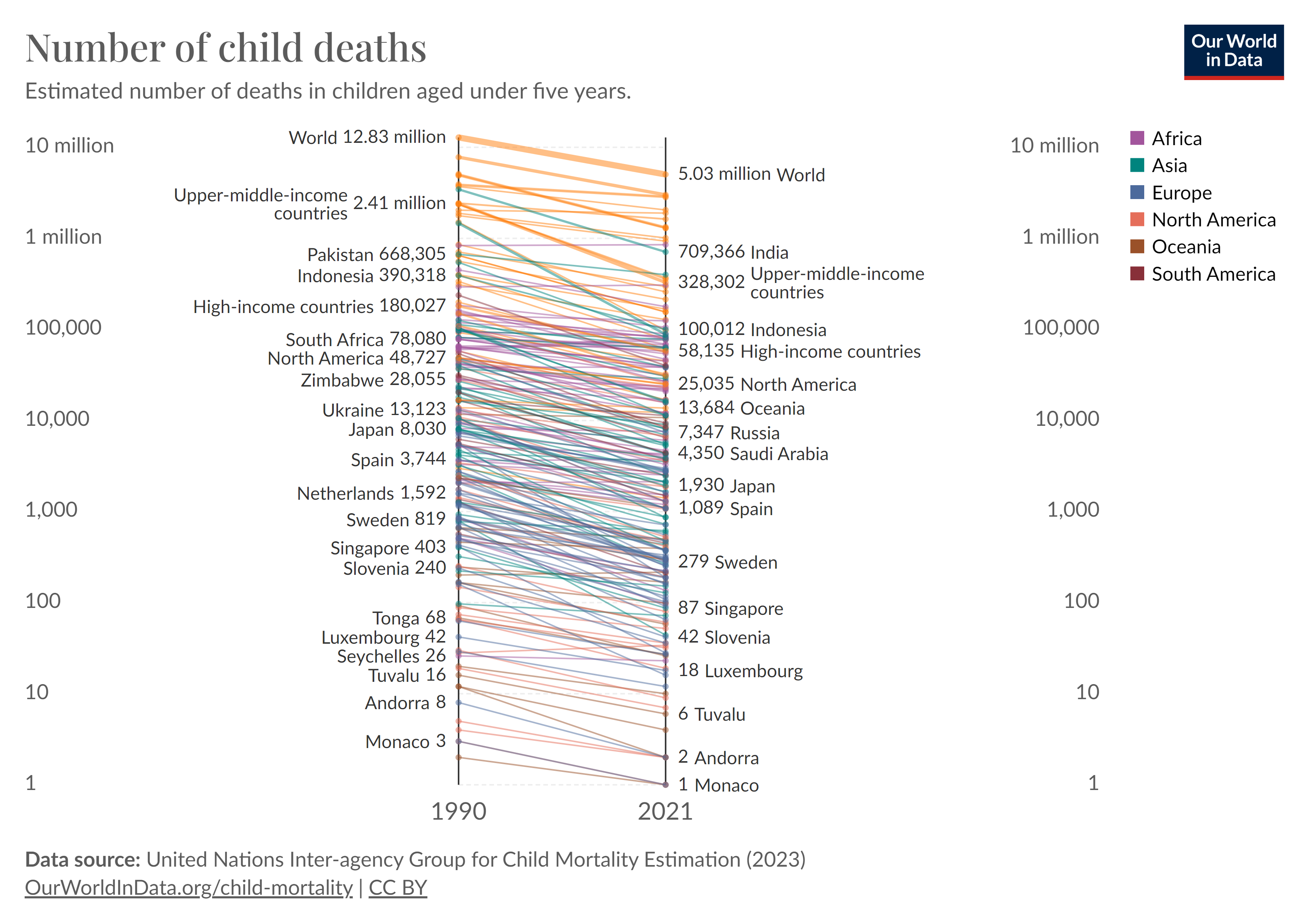

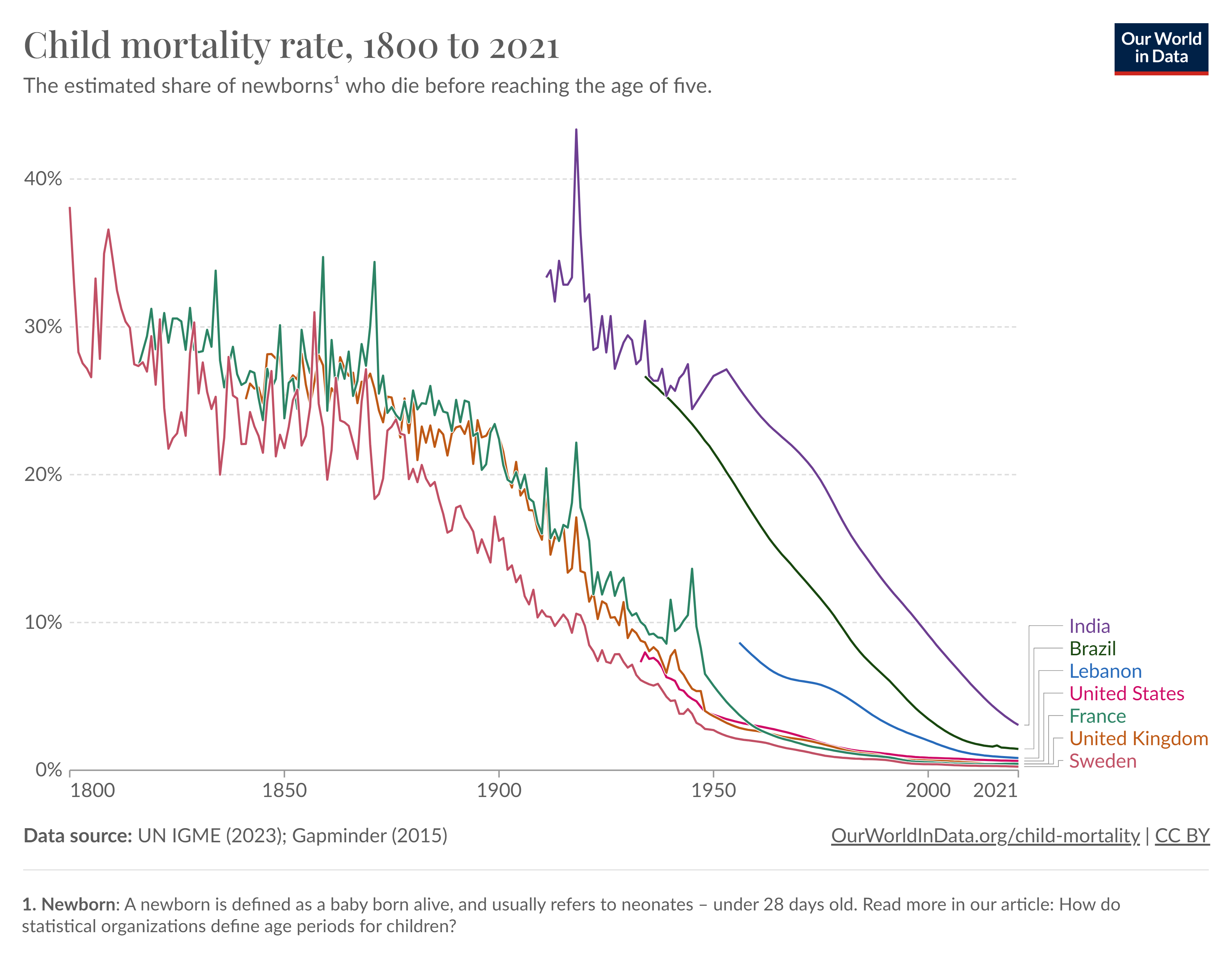

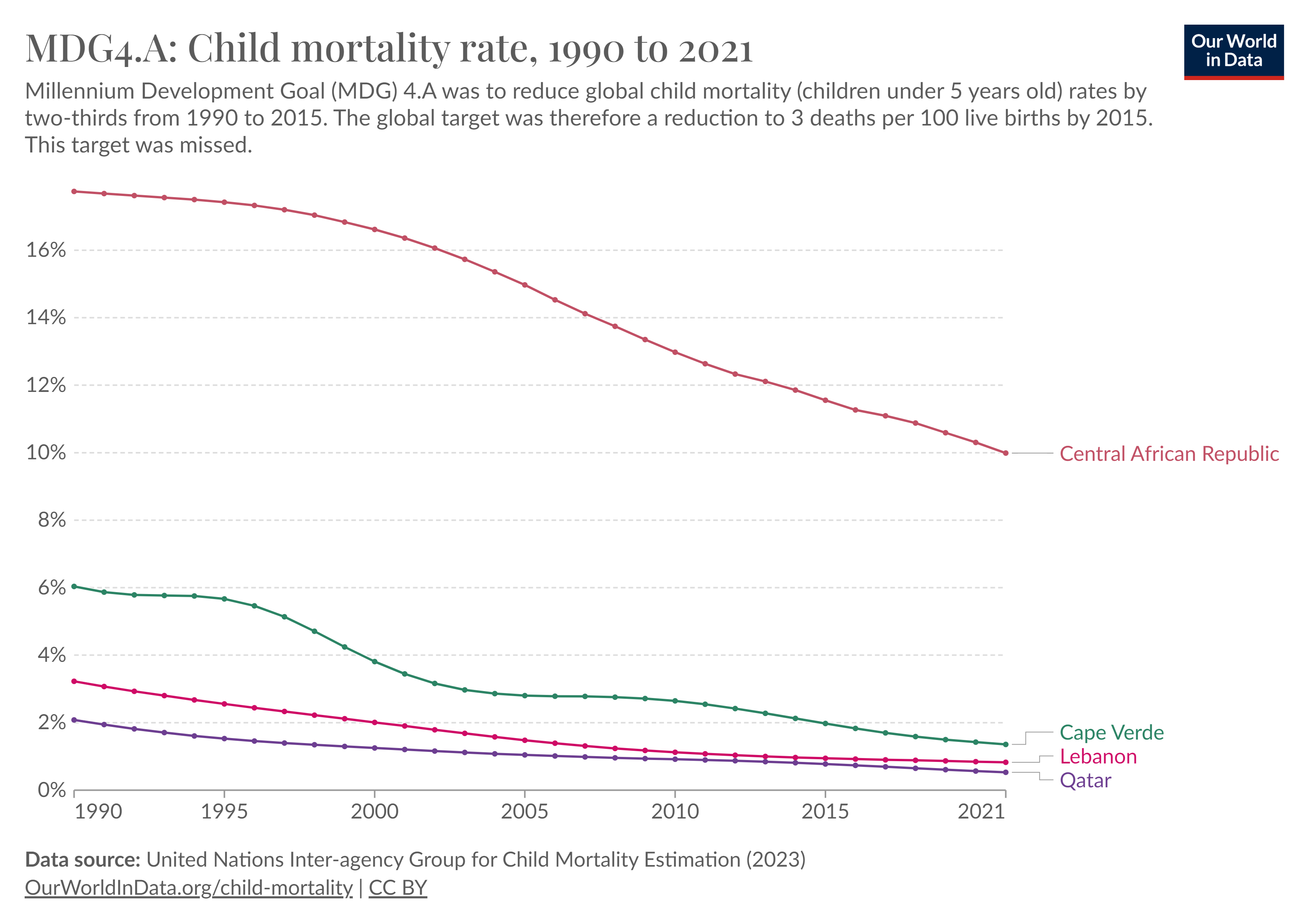

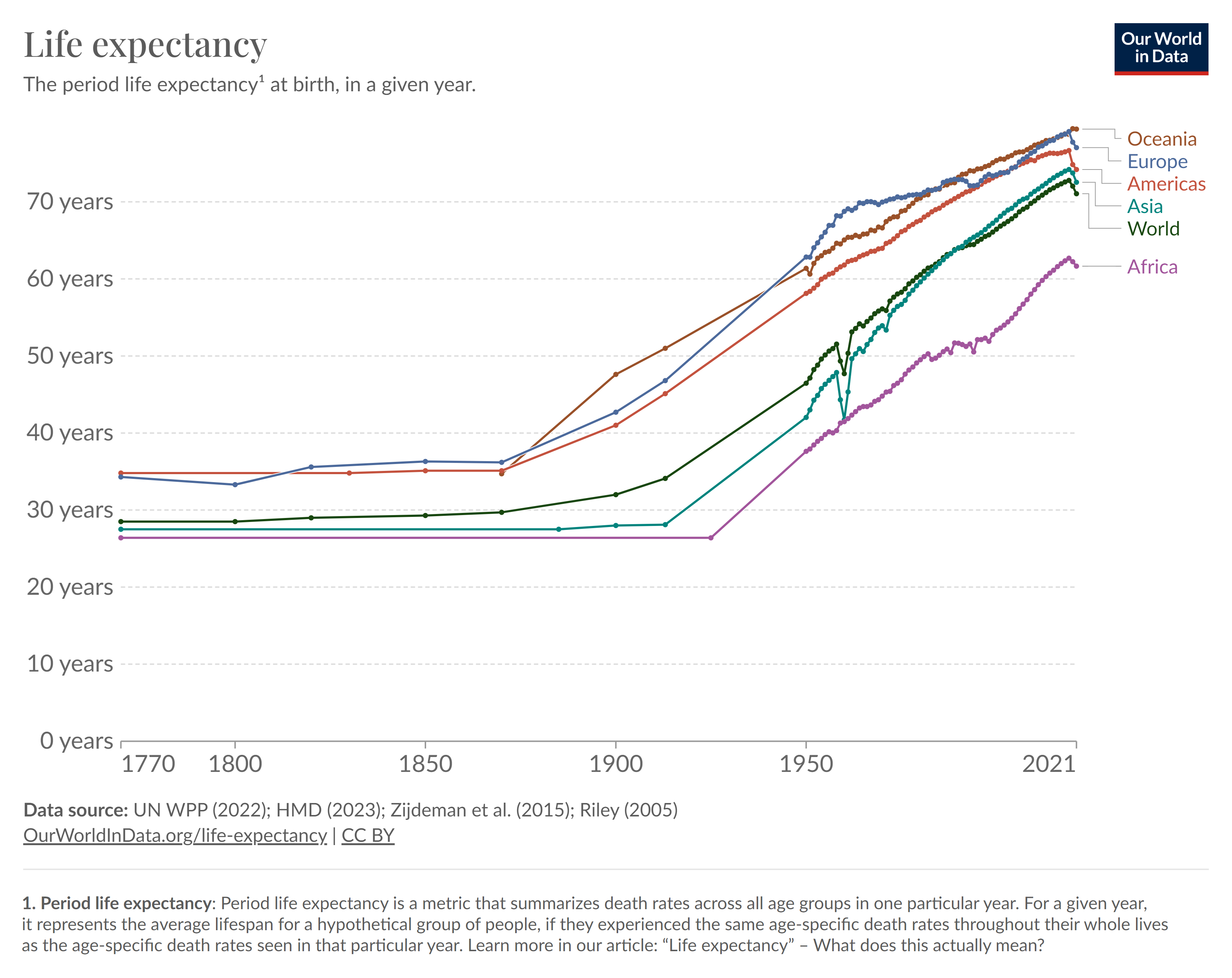

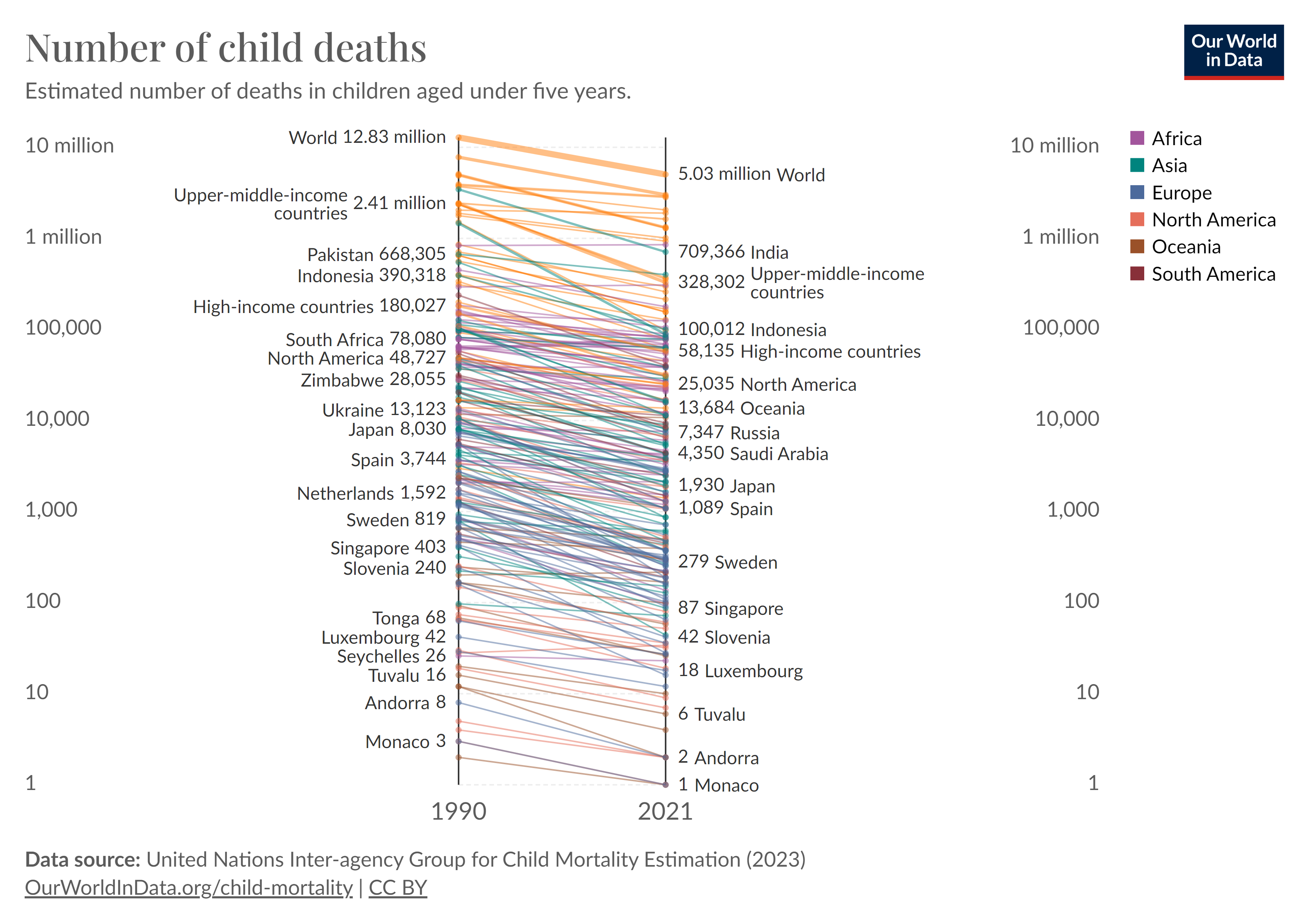

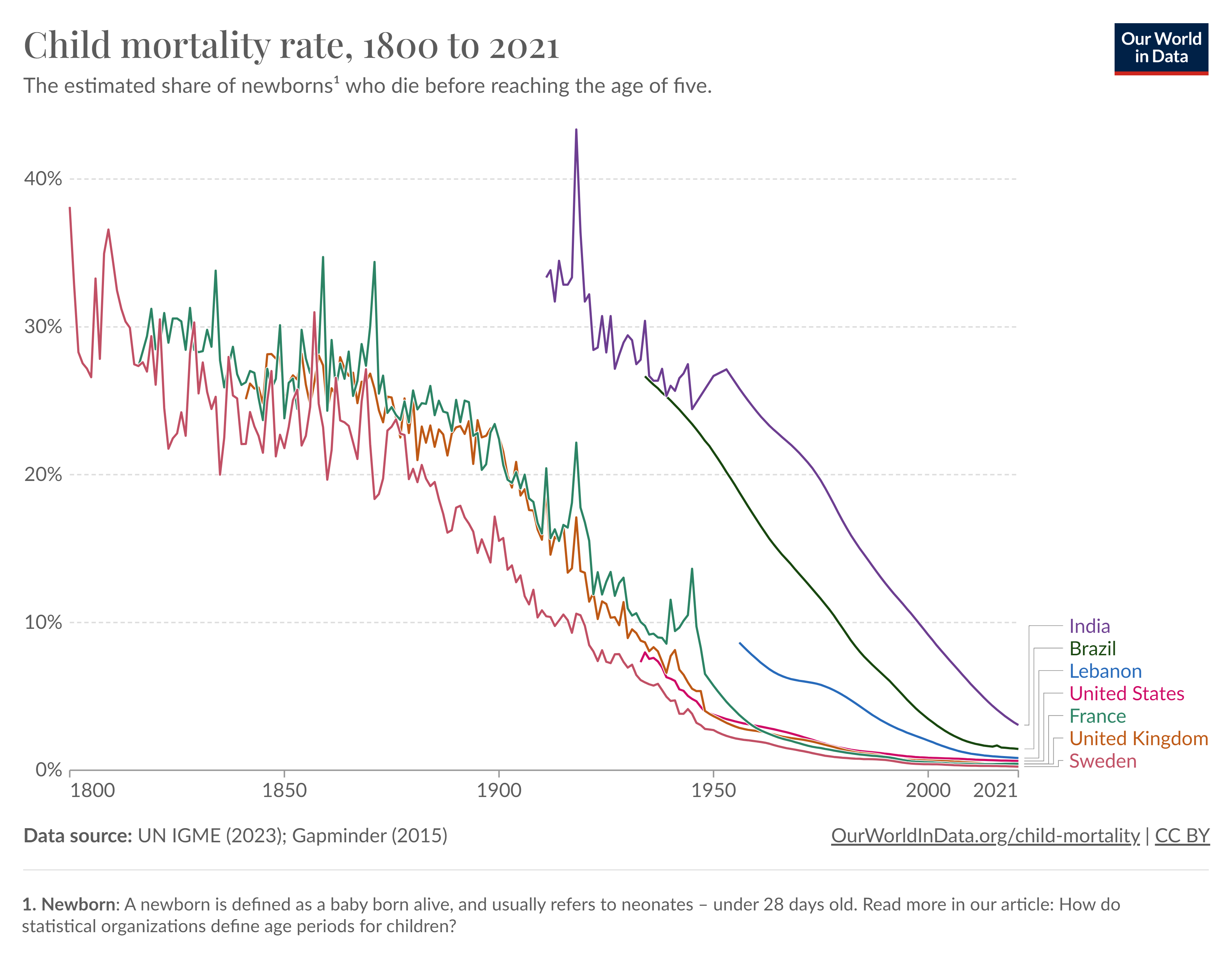

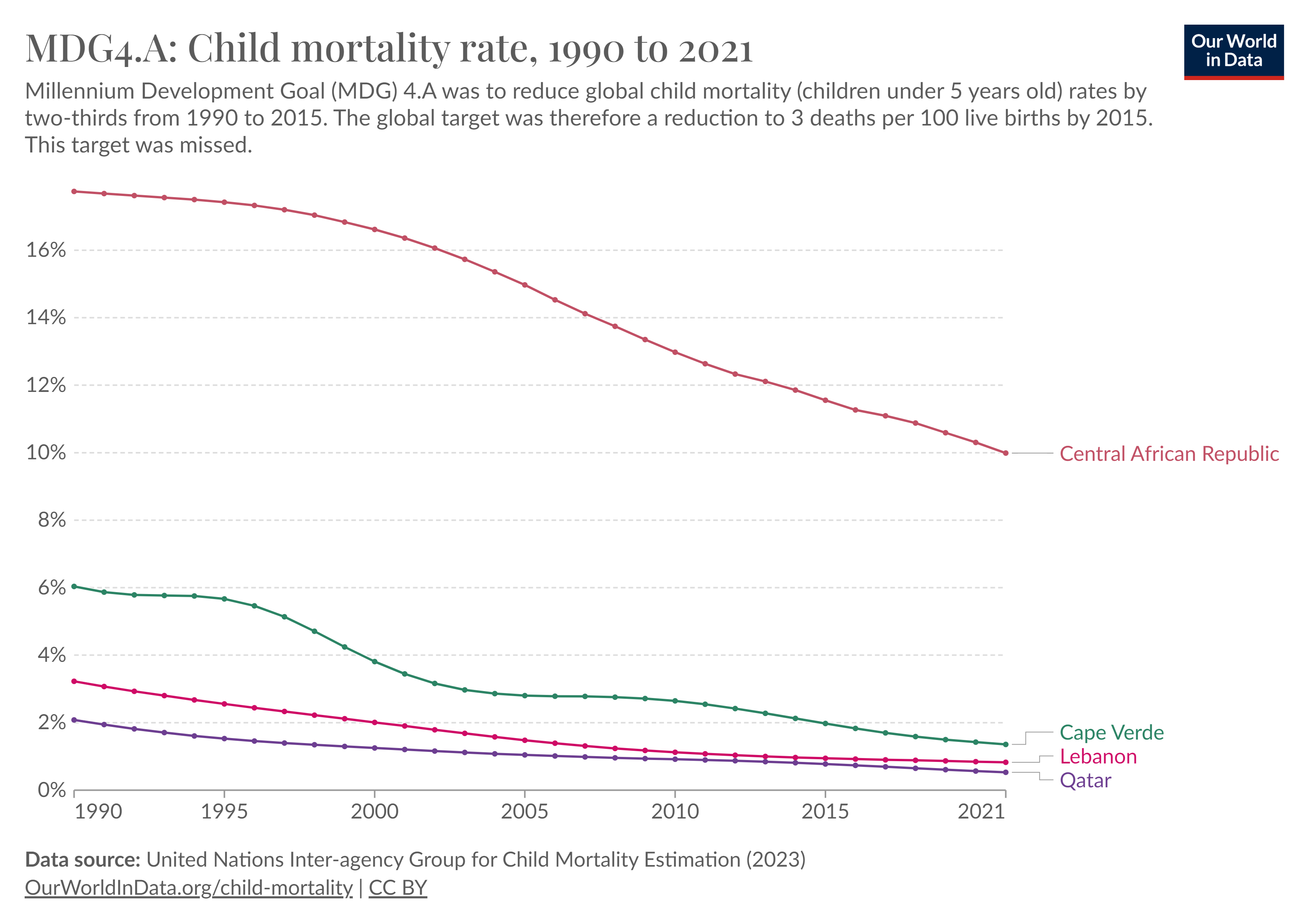

Historical records demonstrate that not only were we experiencing higher mortality rates in the past, but it was predominantly younger individuals who were tragically losing their lives. Life expectancy at birth during the Middle Ages was approximately 30 years, while in the early 20th century, it was about 50 years. This phenomenon was primarily attributed to high infant and child mortality rates due to infectious diseases, malnutrition, and lack of sanitation. Even for those who survived past infancy, a plethora of health hazards lurked at every corner, leading to the premature death of numerous young and middle-aged individuals. Thus, the past was marked by shorter lives, with younger individuals bearing the brunt of mortality.

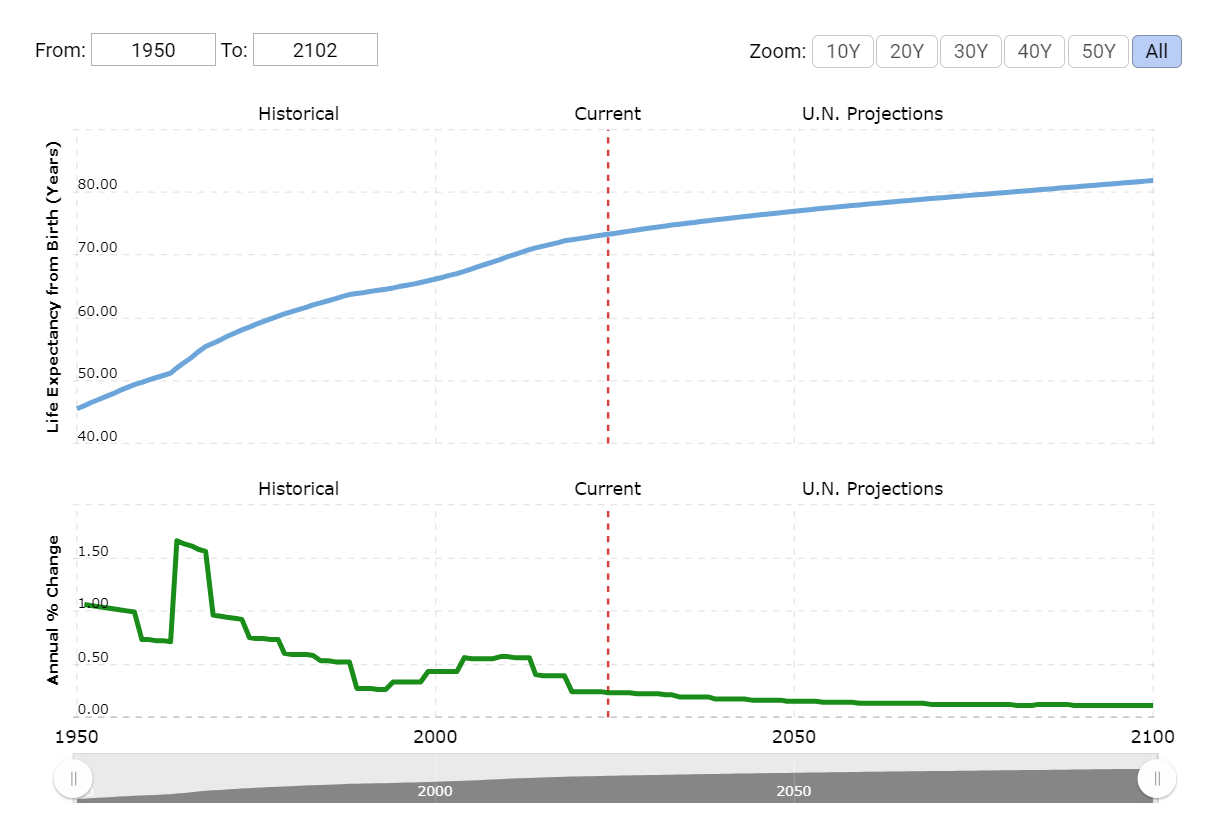

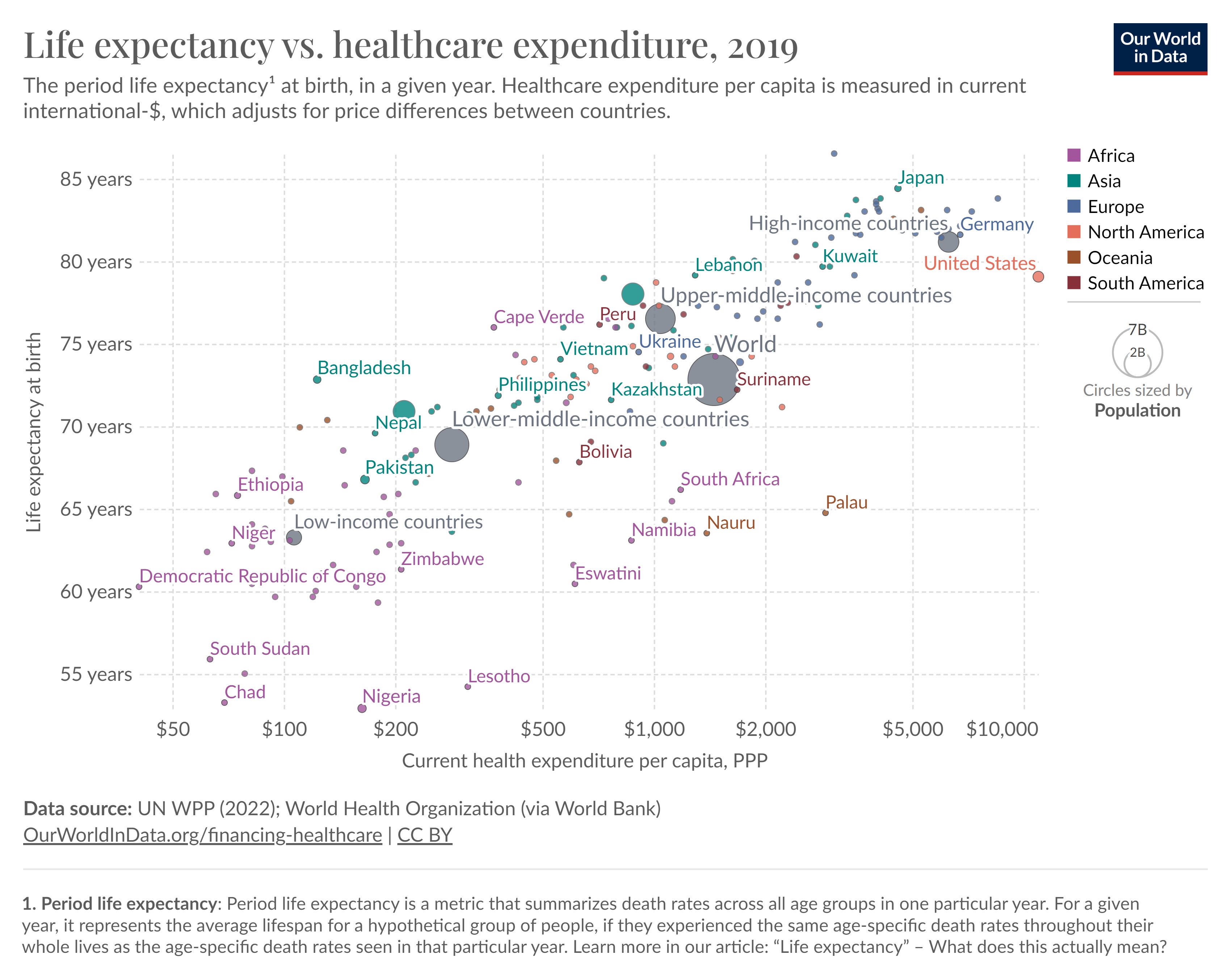

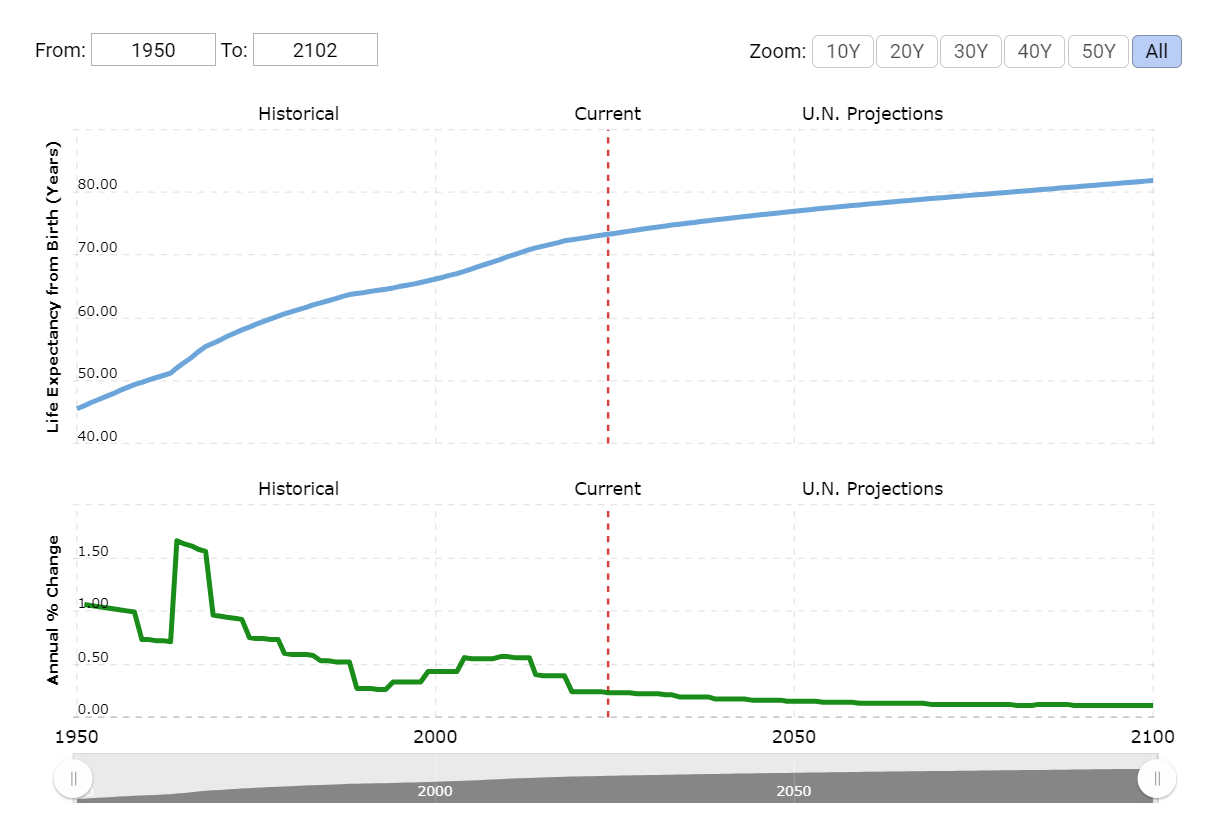

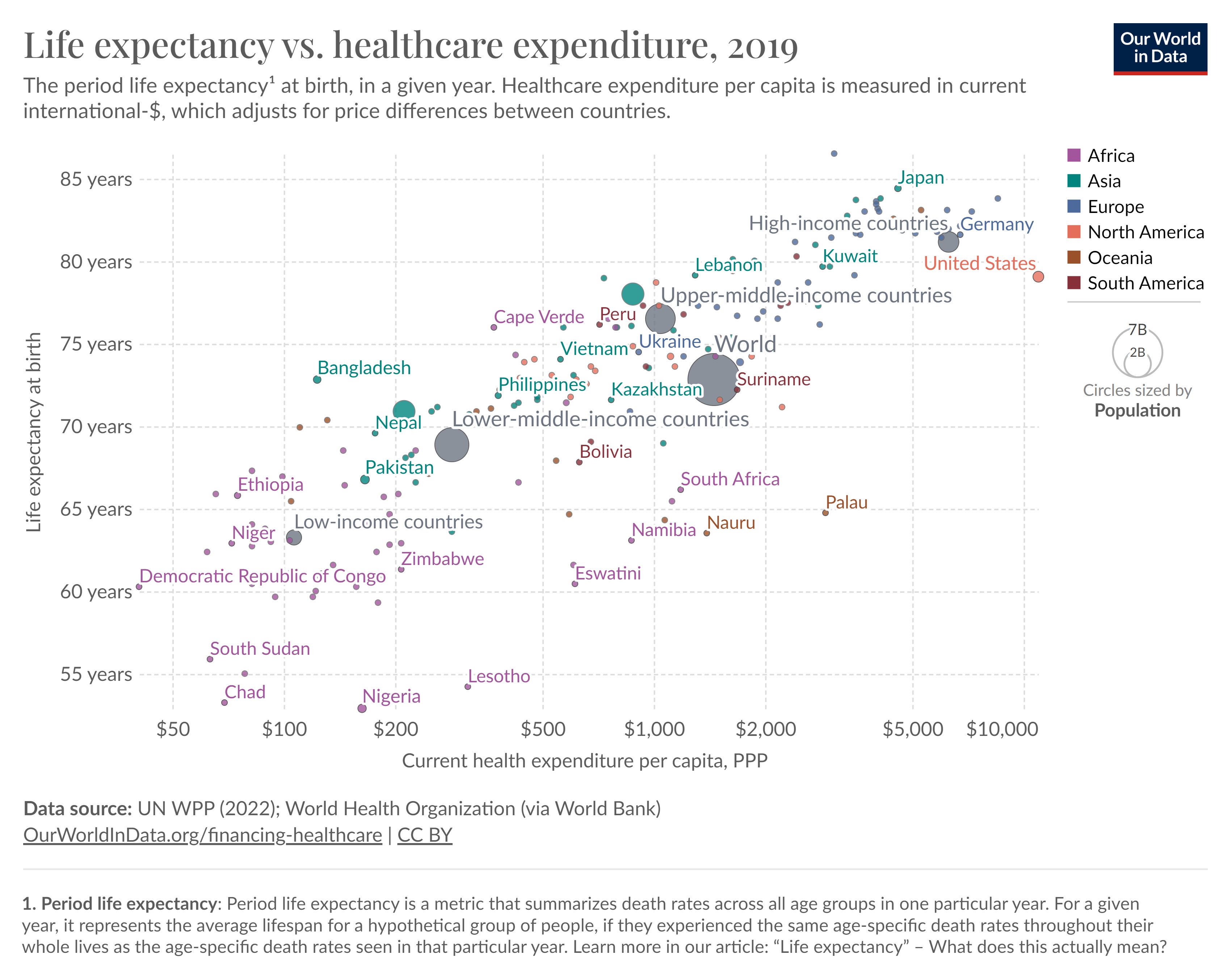

Not only has the global mortality rate decreased significantly in recent years, but the average life expectancy has also witnessed a remarkable increase. This positive trend reflects advancements in healthcare, improved living conditions, and greater access to essential resources, all contributing to a healthier and longer life for people worldwide.

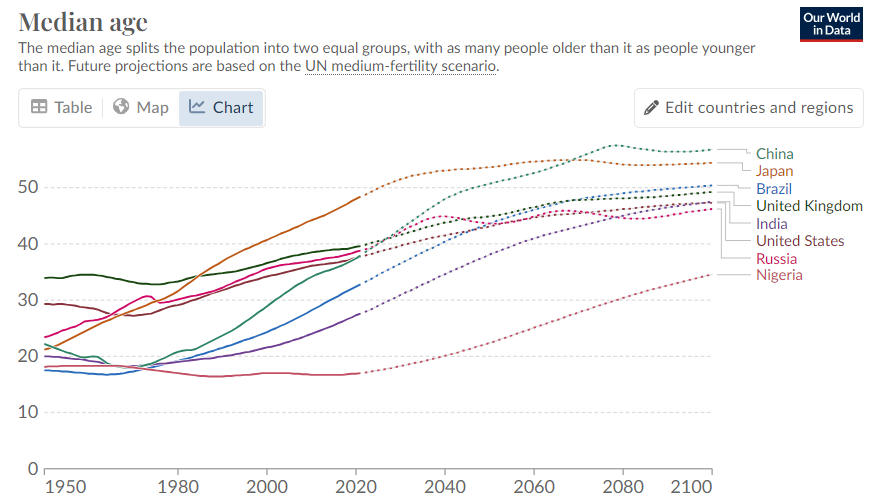

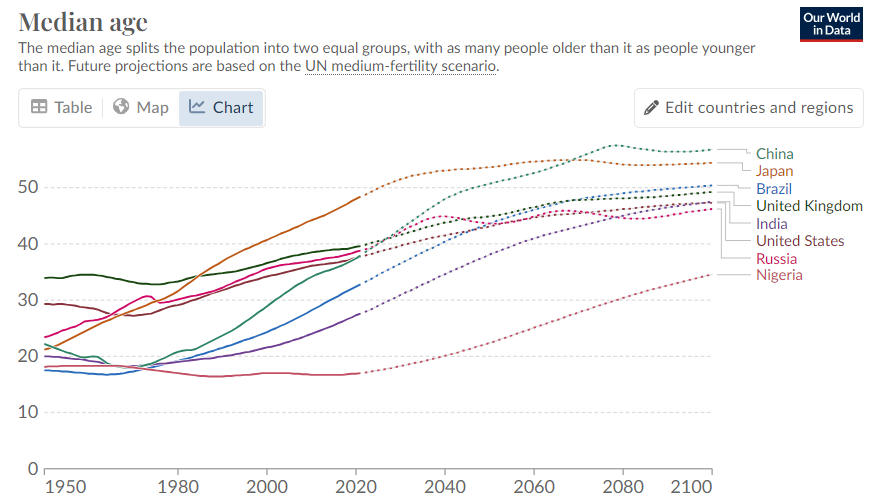

In contemplating the future, it appears that the mortality rate may rise once more. This can be attributed to the fact that our lifespan is increasing while birth rates are declining. Consequently, our population will consist of a larger proportion of older individuals than ever before. As a result, it will be the elderly who will predominantly contribute to the mortality rate, as opposed to younger generations.

The arithmetic of life and death takes an intriguing turn when we factor in longer lifespans and declining birth rates. As people live longer, the demographic structure of our society changes, leaning towards a larger proportion of older individuals. Simultaneously, with fewer children being born, the younger population diminishes. This shift in demographics results in a higher mortality rate dictated primarily by old age rather than disease or other factors that traditionally affected younger populations.

In previous centuries, the graph of mortality was broad-based, with deaths occurring across all age groups. However, the modern era paints a different picture. Mortality is now more “top-heavy,” with a significant proportion of deaths occurring amongst the elderly. This trend projects a future where the death rate, while still lower than in centuries past, may rise due to an increasing proportion of the population reaching old age. Consequently, the death rate may no longer be an accurate gauge of societal health as it once was. Instead, it highlights the triumph of longevity, where death is a function of old age rather than disease or deprivation.

That is precisely why I mentioned that not all death rates are equal. Typically, an increase in the death rate is considered negative. However, if the rise in death rate is predominantly due to natural causes associated with old age, it may not be viewed as unfavorable.

Some would argue that older individuals naturally have a higher mortality rate. However, this perspective is built upon the premise that young people have a significantly lower death rate, a notion we often take for granted in the modern era. Historical accounts reveal a starkly different picture. In times gone by, young people faced alarmingly high mortality rates due to rampant disease, malnutrition, and lack of basic healthcare. Such conditions often led to a tragically high prevalence of infant and child deaths. The transformation we’ve witnessed in survival rates across age groups underscores the remarkable progress we’ve made in healthcare, nutrition, and public safety measures over the centuries. While today’s higher mortality rates among older individuals are inevitable due to biological aging, our collective strides in medical science and public health have allowed more individuals—in particular, young people—to survive and thrive.

It is quite astonishing that our greatest achievement as a species often goes unnoticed or unacknowledged.

Are we more peaceful?

The recent surge in global conflict, particularly those involving the United States, raises serious concerns for many, particularly those opposed to war. The implications of these military engagements are far-reaching and complex, affecting not only the immediate regions in conflict but also extending to other parts of the world, including the United States. As taxpayers, Americans inevitably contribute to the funding of these military operations, which can lead to feelings of complicity and unease. This is particularly relevant for those who are fundamentally opposed to war, creating a dissonance between personal values and state actions. The ethical dilemma posed by these situations encourages us to engage in critical discussions and debates around military intervention and to actively seek peaceful and diplomatic avenues for conflict resolution.

How are we doing when it comes to war? Are things getting worse? The onset of the 21st century has been marred by numerous conflicts including those in Afghanistan, Palestine, Syria, Libya, Yemen, and more. The specter of World War III is increasingly brandished and some pundits even suggest we are already embroiled in it. Major global nuclear powers once again seeming to engage in conflicts through proxies adds a layer of alarming complexity to the situation. However, the heart of this question lies not in merely recounting the current set of circumstances, but in evaluating the trajectory we are on.

To truly understand the impact of war on human life, we need to consider the proportion of the population affected. For instance, World War II, the deadliest conflict in human history, accounted for an estimated 80 million deaths. This staggering number represents approximately 3.7% of the world’s population at that time. In contrast, the Mongol conquests, though resulting in fewer total deaths (around 40 million), represented a larger percentage of the world’s population, estimated at around 17%. This is not to downplay the horrific loss of life during World War II but rather to provide a broader perspective on the destructiveness of wars, past and present. Comparing absolute numbers of fatalities can sometimes obscure the true human cost of these conflicts.

Throughout history, various wars have caused immense death tolls, especially when considering the global population of those times. For instance, the Taiping Rebellion is estimated to have resulted in 20 to 30 million deaths, with some estimates reaching as high as 100 million. Taking a conservative estimate of 25 million, this accounts for a staggering 2% of the Earth’s population at that time. Sadly, the Napoleonic Wars eliminated around 5.5% of the Earth’s population, while the 30 Years War that ended in 1648 eradicated approximately 1% of all human beings.

The Spanish conquest of South and Central America had an even more devastating impact, wiping out 7% of the Earth’s population. During the 1550s, the global population was around 500 million, and the Spanish conquest resulted in the death of approximately 35 million individuals. In terms of the percentage of the global population that died in war, the Spanish conquests were twice as devastating as World War II.

Similarly, the Mongol invasions led to the death of around 35 million people when the Earth’s population was a mere 400 million. This equates to 8.75% of the global population, more than double the mortality rate of World War II. On the other hand, the Crusades wiped out about 1% of the global population.

Historical records also show that approximately 40 million people perished during the Three Kingdoms War between the second and third centuries. With the Earth’s population estimated at around 200 million during this period, the death toll from this war reduced the human population by 20% – a figure equivalent to six times the casualties of World War II.

The 21st century, despite its fair share of conflicts, appears less lethal when compared to past epochs of human history, particularly when assessing the percentage of the global population affected by wars. The Iraq War claimed approximately half a million lives, while the wars in Yemen, Afghanistan, and Syria caused 400,000, 243,000, and 600,000 deaths, respectively. Current estimates for the Ukraine war suggest around 200,000 fatalities. In total, these five major conflicts of the 21st century account for roughly 2 million deaths – a mere 0.025% of the global population. While this figure provides no comfort to those directly affected by these wars, it serves to highlight the relative reduction in war-related death tolls compared to previous centuries.

However, determining our current level of peacefulness goes beyond merely counting the dead. It’s also about acknowledging the lives that have been spared – a factor that cannot be overstated. Despite possessing weapons of unprecedented destructive power, our present-day wars are significantly less deadly than those of the past. This counter-intuitive dynamic underscores a fascinating reality: our technological advancements have given us god-like destructive capabilities, yet we engage in conflicts that are far less lethal than those of our ancestors.

Today’s combatants can be killed by enemies located thousands of miles away or tracked from satellites in space. We have bombs whose power supersedes that of all the ordnance used in World War II by a factor of ten. We could, without doubt, make them even more potent, but why bother when we already possess the capacity to annihilate all life on Earth multiple times over? It’s an ironic paradox – our ability to inflict death on a massive scale has never been greater, yet we kill fewer people than ever before. These seemingly contradictory facts are, in reality, closely intertwined, suggesting a trend toward a more peaceful existence.

Lastly, the Punic Wars resulted in about 1.5 million deaths, representing around 1% of the Earth’s population at that time. These massive wars, which wiped out 20%, 7%, 3%, etc., of the Earth’s population, serve as a sobering reminder of the devastating impact of conflicts throughout history.

When it comes to the percentage of the global population killed, the death tolls from major conflicts in the 21st century – like the wars in Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, Syria, and Ukraine – would have to be multiplied by a whopping 140 times to match the devastation caused by World War II. It puts into perspective just how massive World War II was and reminds us that wars back then claimed a much larger portion of the human population.

And here’s something mind-blowing: to equal the destruction caused by the Three Kingdoms War in terms of the percentage of the global population killed, the death rates of 21st-century wars would need to be multiplied by a staggering 800 times. The Three Kingdoms War, which took place when the world’s population was way smaller, resulted in a death toll that reduced the population by 20 percent – a figure that’s hard to imagine in today’s context of conflicts. These comparisons give us a reality check, showing how we’ve made progress towards a less violent world while reminding us of the devastating potential of war.

It’s mind-boggling to think about our incredible capacity for destruction, yet our remarkable restraint in actually using it. We’re armed with weapons that our ancestors could only dream of, and they would have probably jumped at the chance to unleash such power. We can obliterate entire cities in an instant, and wreak havoc on ecosystems for generations, and yet, we choose not to. It’s a paradox. We recognize the horrifying implications of our actions and the fact that we’re all in this together. This realization gives us a glimmer of hope that maybe, just maybe, we’re heading towards a more peaceful world. A world where war and destruction become a thing of the past.

Are we freer?

Are we freer? This question proves significantly more difficult to answer, as freedom is a complex, multifaceted concept that goes beyond mere statistics. The reality of freedom hinges greatly on personal identities and geographical locations; it is a commodity available in varying degrees to different people.

In some societies, legal provisions safeguard individual liberties, thus ensuring a high degree of freedom. However, in other regions, oppressive regimes curtail these liberties, leaving the populace languishing in the throes of tyranny. Moreover, it isn’t just legal systems that dictate the level of freedom; circumstances such as economic conditions, societal norms, and cultural biases also play substantial roles.

The concept of freedom, therefore, is not universally experienced but is often a product of one’s environment, identity, and circumstances. It’s an intricate interplay of myriad factors that continue to shape and redefine the parameters of freedom in the 21st century.

In contemporary discussions, the term ‘freedom’ is often thrown around as a political slogan, a rallying cry, or a marketing buzzword, seemingly detached from its profound implications and complexities. This casual usage can sometimes dilute the significant meaning of the concept. True freedom, however, extends beyond the mere absence of restrictions; it encompasses the capacity to think, express, and act without undue interference or fear. Its application and experience are deeply personal, molded by sociocultural, economic, and political contexts. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of ‘freedom’ requires a nuanced appreciation of these intricacies, rather than a superficial adoption of the term as a catchphrase.

Contemporary discussions often revolve around the perceived loss of basic freedoms like freedom of speech, association, and religion. But here’s the thing: these freedoms are interconnected and can sometimes clash. For example, unrestricted speech can invade someone’s privacy, or religious freedom can clash with someone else’s beliefs. So, when one person gains freedom at the expense of another, is it really a win? This question highlights the delicate balance needed to protect individual liberties and create a fair society.

Is our society on the verge of collapsing? Are things getting better or worse?

This brings to light the intriguing paradox of societal perception. While many agree that society is declining, the reasons behind this belief vary greatly depending on one’s political standpoint. Some argue that the erosion of traditional values and structures is the main issue, while others attribute it to social inequality or environmental degradation. This difference in opinion highlights the complexity of societal problems and the challenge of identifying single causes for perceived societal decline.

These divergent views often result in a blame game that further complicates the situation. Each side perceives itself as the solution – the proverbial ‘cure’ to societal woes – while casting the other as the root cause of the problems. This cyclical pattern of blame and counter-blame exacerbates divisions and hampers efforts toward constructive dialogues and solutions. The perception of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ echoes through each aspect of societal debates, underscoring the complexities in addressing multifaceted societal issues.

To assess these societal concerns objectively, it’s essential to delve into credible data sources and analyze them critically. For instance, if we look at the allegations of moral decay, do the crime rates, instances of violence, or other quantifiable factors support this claim? Moreover, as we evaluate the argument that environmental degradation is spurring societal decline, we need to consider scientific studies that examine the impact of climate change on our societies. Similarly, analyzing income distribution statistics can shed light on the claims about growing social inequality. It’s only through careful examination of such empirical evidence that we can ascertain the validity of these narratives and establish a more grounded understanding of societal trends. This data-centric approach may not offer the complete picture, but it adds an essential layer of objectivity to our discussions, offering a solid foundation for productive dialogues and potential solutions.

In the sphere of societal discussions, explanations grounded in empirical evidence often hold more weight than mere narratives. Narratives, though useful in conveying complex ideas and invoking empathy, risk oversimplification of multifaceted societal issues and may be influenced by biases. Conversely, explanations that are founded on data and critical analysis add an element of objectivity, fostering informed dialogues. These explanations provide a more accurate reflection of societal trends and can guide effective policymaking. However, it’s crucial to remember that while data-driven explanations are vital, they must be communicated effectively. The marriage of accurate, objective explanations with compelling narratives can lead to a more nuanced understanding of societal issues and drive meaningful change.

8 Key Questions to Assess Potential Societal Collapse

I have formulated eight questions that I believe serve as reliable indicators of the state of society, regardless of one’s political inclinations. While I intended to select questions that can be answered with measurable data, I acknowledge that some of them may be more ambiguous than others. Nonetheless, I sought to retain the essence of the original meaning while enhancing the overall quality of the writing in terms of word choice, structure, readability, and eloquence.

- Are we dying less?

- Are we living longer?

- Are we more peaceful?

- Are we freer?

- Are we committing fewer crimes?

- Are we more prosperous?

- Are we more knowledgeable?

- Are we happier?

You might instinctively think that you know the answers to these questions, but you may be surprised when confronted with actual data. Our perceptions are often influenced by personal experiences and the media, which may not accurately represent the broader societal trends. It’s important to approach these questions with an open mind, putting aside preconceived notions and biases. Remember, our objective here is not to validate our perspectives but to seek a clearer understanding of the societal landscape. Therefore, we will delve into these questions, armed with curiosity and a willingness to challenge our beliefs.

Are We Dying Less?

According to the World Bank, worldwide death rates have significantly declined from 1960 to 2020. This statistic, expressed as the number of deaths per 1000 people, provides a good measure of general health and the quality of life across the globe.

In 1960, the global death rate stood at approximately 17.9 deaths per 1000 people. As of 2020, this number has dropped to around 7.6 deaths per 1000 people. This decline in death rate over the past six decades is a testament to numerous factors including advancements in healthcare, improvements in living conditions, and effective public health policies and programs. The data serves as empirical evidence that, in terms of mortality rate, we are certainly faring better now than in the past.

While exact figures from centuries past may not be readily available, various historical records and studies indicate that the death rate was significantly higher than what we observe today. For instance, it’s documented that infectious diseases such as the bubonic plague, Spanish flu, and numerous outbreaks of cholera claimed millions of lives, contributing to a high death rate. Moreover, lack of access to modern healthcare, poor living conditions, and frequent wars also led to increased mortality. Although it’s challenging to extrapolate precise figures from these historical accounts, the consensus among historians and demographers aligns with the notion of a considerably higher death rate in the past. This trend underscores the progress humanity has made over the centuries in enhancing life expectancy and reducing the death rate.

At the turn of the 20th century, the statistics were quite grim. A person had a staggering one in three chance of dying from pneumonia, tuberculosis, or diarrhea. This reality was faced just a little over a hundred years ago. These diseases, which are now largely preventable and treatable due to advancements in healthcare and sanitation, were once considered a death sentence. It’s a somber reflection of the state of public health merely a century ago, highlighting the significant strides we’ve made in improving human health and longevity.

However, it must be noted that not all death rates are created equally. This brings into sharp focus the even grimmer realities of the past. Our ancestors had a significantly lower life expectancy compared to ours today. The fact that people weren’t living as long as they do today fundamentally skews our understanding of historical death rates. The advancements in medical science, sanitation, nutrition, and safety regulations have played pivotal roles in extending the human lifespan. These improvements have not only caused a decline in mortality rates but also have enabled more and more individuals to live into old age.

This leads us to the second question.

Are We Living Longer?

Historical records demonstrate that not only were we experiencing higher mortality rates in the past, but it was predominantly younger individuals who were tragically losing their lives. Life expectancy at birth during the Middle Ages was approximately 30 years, while in the early 20th century, it was about 50 years. This phenomenon was primarily attributed to high infant and child mortality rates due to infectious diseases, malnutrition, and lack of sanitation. Even for those who survived past infancy, a plethora of health hazards lurked at every corner, leading to the premature death of numerous young and middle-aged individuals. Thus, the past was marked by shorter lives, with younger individuals bearing the brunt of mortality.

Not only has the global mortality rate decreased significantly in recent years, but the average life expectancy has also witnessed a remarkable increase. This positive trend reflects advancements in healthcare, improved living conditions, and greater access to essential resources, all contributing to a healthier and longer life for people worldwide.

In contemplating the future, it appears that the mortality rate may rise once more. This can be attributed to the fact that our lifespan is increasing while birth rates are declining. Consequently, our population will consist of a larger proportion of older individuals than ever before. As a result, it will be the elderly who will predominantly contribute to the mortality rate, as opposed to younger generations.

The arithmetic of life and death takes an intriguing turn when we factor in longer lifespans and declining birth rates. As people live longer, the demographic structure of our society changes, leaning towards a larger proportion of older individuals. Simultaneously, with fewer children being born, the younger population diminishes. This shift in demographics results in a higher mortality rate dictated primarily by old age rather than disease or other factors that traditionally affected younger populations.

In previous centuries, the graph of mortality was broad-based, with deaths occurring across all age groups. However, the modern era paints a different picture. Mortality is now more “top-heavy,” with a significant proportion of deaths occurring amongst the elderly. This trend projects a future where the death rate, while still lower than in centuries past, may rise due to an increasing proportion of the population reaching old age. Consequently, the death rate may no longer be an accurate gauge of societal health as it once was. Instead, it highlights the triumph of longevity, where death is a function of old age rather than disease or deprivation.

That is precisely why I mentioned that not all death rates are equal. Typically, an increase in the death rate is considered negative. However, if the rise in death rate is predominantly due to natural causes associated with old age, it may not be viewed as unfavorable.

Some would argue that older individuals naturally have a higher mortality rate. However, this perspective is built upon the premise that young people have a significantly lower death rate, a notion we often take for granted in the modern era. Historical accounts reveal a starkly different picture. In times gone by, young people faced alarmingly high mortality rates due to rampant disease, malnutrition, and lack of basic healthcare. Such conditions often led to a tragically high prevalence of infant and child deaths. The transformation we’ve witnessed in survival rates across age groups underscores the remarkable progress we’ve made in healthcare, nutrition, and public safety measures over the centuries. While today’s higher mortality rates among older individuals are inevitable due to biological aging, our collective strides in medical science and public health have allowed more individuals—in particular, young people—to survive and thrive.

It is quite astonishing that our greatest achievement as a species often goes unnoticed or unacknowledged.

Are we more peaceful?

The recent surge in global conflict, particularly those involving the United States, raises serious concerns for many, particularly those opposed to war. The implications of these military engagements are far-reaching and complex, affecting not only the immediate regions in conflict but also extending to other parts of the world, including the United States. As taxpayers, Americans inevitably contribute to the funding of these military operations, which can lead to feelings of complicity and unease. This is particularly relevant for those who are fundamentally opposed to war, creating a dissonance between personal values and state actions. The ethical dilemma posed by these situations encourages us to engage in critical discussions and debates around military intervention and to actively seek peaceful and diplomatic avenues for conflict resolution.

How are we doing when it comes to war? Are things getting worse? The onset of the 21st century has been marred by numerous conflicts including those in Afghanistan, Palestine, Syria, Libya, Yemen, and more. The specter of World War III is increasingly brandished and some pundits even suggest we are already embroiled in it. Major global nuclear powers once again seeming to engage in conflicts through proxies adds a layer of alarming complexity to the situation. However, the heart of this question lies not in merely recounting the current set of circumstances, but in evaluating the trajectory we are on.

To truly understand the impact of war on human life, we need to consider the proportion of the population affected. For instance, World War II, the deadliest conflict in human history, accounted for an estimated 80 million deaths. This staggering number represents approximately 3.7% of the world’s population at that time. In contrast, the Mongol conquests, though resulting in fewer total deaths (around 40 million), represented a larger percentage of the world’s population, estimated at around 17%. This is not to downplay the horrific loss of life during World War II but rather to provide a broader perspective on the destructiveness of wars, past and present. Comparing absolute numbers of fatalities can sometimes obscure the true human cost of these conflicts.

Throughout history, various wars have caused immense death tolls, especially when considering the global population of those times. For instance, the Taiping Rebellion is estimated to have resulted in 20 to 30 million deaths, with some estimates reaching as high as 100 million. Taking a conservative estimate of 25 million, this accounts for a staggering 2% of the Earth’s population at that time. Sadly, the Napoleonic Wars eliminated around 5.5% of the Earth’s population, while the 30 Years War that ended in 1648 eradicated approximately 1% of all human beings.

The Spanish conquest of South and Central America had an even more devastating impact, wiping out 7% of the Earth’s population. During the 1550s, the global population was around 500 million, and the Spanish conquest resulted in the death of approximately 35 million individuals. In terms of the percentage of the global population that died in war, the Spanish conquests were twice as devastating as World War II.

Similarly, the Mongol invasions led to the death of around 35 million people when the Earth’s population was a mere 400 million. This equates to 8.75% of the global population, more than double the mortality rate of World War II. On the other hand, the Crusades wiped out about 1% of the global population.

Historical records also show that approximately 40 million people perished during the Three Kingdoms War between the second and third centuries. With the Earth’s population estimated at around 200 million during this period, the death toll from this war reduced the human population by 20% – a figure equivalent to six times the casualties of World War II.

The 21st century, despite its fair share of conflicts, appears less lethal when compared to past epochs of human history, particularly when assessing the percentage of the global population affected by wars. The Iraq War claimed approximately half a million lives, while the wars in Yemen, Afghanistan, and Syria caused 400,000, 243,000, and 600,000 deaths, respectively. Current estimates for the Ukraine war suggest around 200,000 fatalities. In total, these five major conflicts of the 21st century account for roughly 2 million deaths – a mere 0.025% of the global population. While this figure provides no comfort to those directly affected by these wars, it serves to highlight the relative reduction in war-related death tolls compared to previous centuries.

However, determining our current level of peacefulness goes beyond merely counting the dead. It’s also about acknowledging the lives that have been spared – a factor that cannot be overstated. Despite possessing weapons of unprecedented destructive power, our present-day wars are significantly less deadly than those of the past. This counter-intuitive dynamic underscores a fascinating reality: our technological advancements have given us god-like destructive capabilities, yet we engage in conflicts that are far less lethal than those of our ancestors.

Today’s combatants can be killed by enemies located thousands of miles away or tracked from satellites in space. We have bombs whose power supersedes that of all the ordnance used in World War II by a factor of ten. We could, without doubt, make them even more potent, but why bother when we already possess the capacity to annihilate all life on Earth multiple times over? It’s an ironic paradox – our ability to inflict death on a massive scale has never been greater, yet we kill fewer people than ever before. These seemingly contradictory facts are, in reality, closely intertwined, suggesting a trend toward a more peaceful existence.

Lastly, the Punic Wars resulted in about 1.5 million deaths, representing around 1% of the Earth’s population at that time. These massive wars, which wiped out 20%, 7%, 3%, etc., of the Earth’s population, serve as a sobering reminder of the devastating impact of conflicts throughout history.

When it comes to the percentage of the global population killed, the death tolls from major conflicts in the 21st century – like the wars in Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, Syria, and Ukraine – would have to be multiplied by a whopping 140 times to match the devastation caused by World War II. It puts into perspective just how massive World War II was and reminds us that wars back then claimed a much larger portion of the human population.

And here’s something mind-blowing: to equal the destruction caused by the Three Kingdoms War in terms of the percentage of the global population killed, the death rates of 21st-century wars would need to be multiplied by a staggering 800 times. The Three Kingdoms War, which took place when the world’s population was way smaller, resulted in a death toll that reduced the population by 20 percent – a figure that’s hard to imagine in today’s context of conflicts. These comparisons give us a reality check, showing how we’ve made progress towards a less violent world while reminding us of the devastating potential of war.

It’s mind-boggling to think about our incredible capacity for destruction, yet our remarkable restraint in actually using it. We’re armed with weapons that our ancestors could only dream of, and they would have probably jumped at the chance to unleash such power. We can obliterate entire cities in an instant, and wreak havoc on ecosystems for generations, and yet, we choose not to. It’s a paradox. We recognize the horrifying implications of our actions and the fact that we’re all in this together. This realization gives us a glimmer of hope that maybe, just maybe, we’re heading towards a more peaceful world. A world where war and destruction become a thing of the past.

Are we freer?

Are we freer? This question proves significantly more difficult to answer, as freedom is a complex, multifaceted concept that goes beyond mere statistics. The reality of freedom hinges greatly on personal identities and geographical locations; it is a commodity available in varying degrees to different people.

In some societies, legal provisions safeguard individual liberties, thus ensuring a high degree of freedom. However, in other regions, oppressive regimes curtail these liberties, leaving the populace languishing in the throes of tyranny. Moreover, it isn’t just legal systems that dictate the level of freedom; circumstances such as economic conditions, societal norms, and cultural biases also play substantial roles.

The concept of freedom, therefore, is not universally experienced but is often a product of one’s environment, identity, and circumstances. It’s an intricate interplay of myriad factors that continue to shape and redefine the parameters of freedom in the 21st century.

In contemporary discussions, the term ‘freedom’ is often thrown around as a political slogan, a rallying cry, or a marketing buzzword, seemingly detached from its profound implications and complexities. This casual usage can sometimes dilute the significant meaning of the concept. True freedom, however, extends beyond the mere absence of restrictions; it encompasses the capacity to think, express, and act without undue interference or fear. Its application and experience are deeply personal, molded by sociocultural, economic, and political contexts. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of ‘freedom’ requires a nuanced appreciation of these intricacies, rather than a superficial adoption of the term as a catchphrase.

Contemporary discussions often revolve around the perceived loss of basic freedoms like freedom of speech, association, and religion. But here’s the thing: these freedoms are interconnected and can sometimes clash. For example, unrestricted speech can invade someone’s privacy, or religious freedom can clash with someone else’s beliefs. So, when one person gains freedom at the expense of another, is it really a win? This question highlights the delicate balance needed to protect individual liberties and create a fair society.

![1791 - Freedom of speech, press, religi[on], assem[bly]; 1941 - Freedom of expression and religion,](https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/pnp/ppmsca/18500/18563r.jpg)